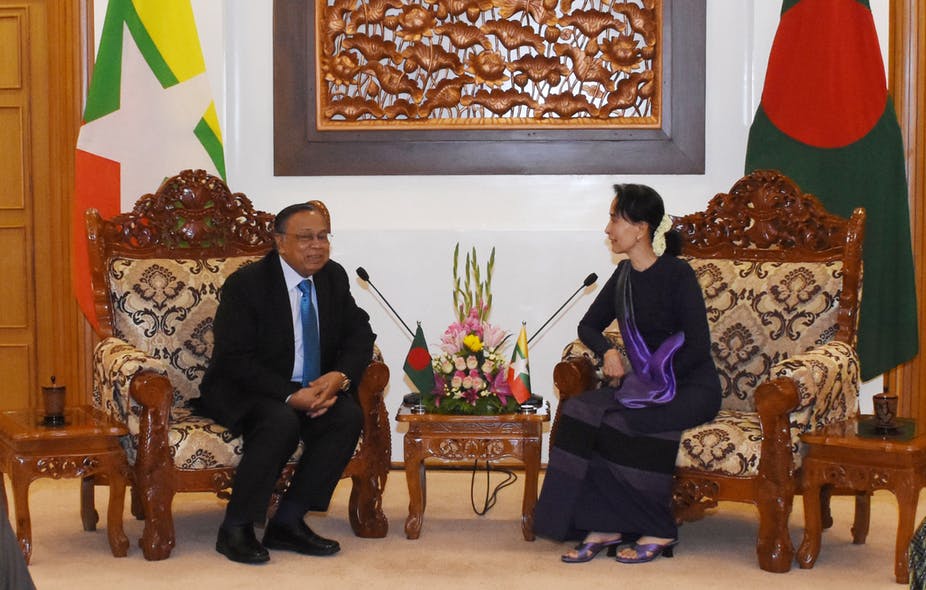

A deal done: the foreign minister of Bangladesh, Abul Hassan Mahmud Ali, visits Myanmar State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi. EPA/Myanmar Ministry of Information

Rosa Freedman, University of Reading

Many Rohingya people who have fled the ethnic cleansing in Myanmar are now living as refugees in Bangladesh. And now, the two countries have reportedly struck a deal to return them home. Returning Rohingya people to the hands of their persecutors not only violates international law, it raises fundamental questions about how the world protects those fleeing the most heinous crimes and abuses.

This deal comes just days after Ratko Mladic was sentenced to life imprisonment for his role in the Srebrenica massacre, which took place in Bosnia even as news cameras broadcast footage around the world – in much the same way as they have documented this latest crisis of ethnic cleansing.

As far as Myanmar is concerned, the deal will ease the increasing pressure it faces from both the United Nations and its Asian neighbours. The Myanmar government has no interest in welcoming Rohingya refugees home with open arms; those Rohingya who remain in Myanmar are treated as an alien people, denied citizenship and basic rights, and systematically persecuted. The Myanmar government maintains that the recent spike in violence did not amount to ethnic cleansing, that it was not state-sponsored, sanctioned or condoned, and that the Rohingya are safe to return. But those words are empty.

Abundant first-hand reports and documentary footage all point to the same thing: ethnic cleansing conducted by state actors. Top UN officials have been using the term “ethnic cleansing” for some time, and the US secretary of state, Rex Tillerson, is now using it too.

Given that Myanmar is refusing to take responsibility for the atrocities, let alone to provide guarantees of protection and justice for the Rohingya, it beggars belief not just that the country is asking those refugees to return, but that Bangladesh would provide its support.

Under international law, refugees who flee atrocities are afforded fundamental protections. Above all, they are protected by the principles of offering asylum and of non-refoulement – protection against return to a country where a person has reason to fear persecution.

Bangladesh will of course insist that Myanmar wants these people to return, and that only those choosing to do so voluntarily will be returned. But that ignores the facts on the ground. Rohingya refugees’ options are bleak: remain in the squalid camps, somehow escape into Bangladeshi society with no formal documentation or status, or return home and face persecution.

Bleak future

Bangladesh has not acceded to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol. The country has no law to regulate the administration of refugee affairs or guarantee refugees’ rights. And despite many decades of persecution and abuses in Myanmar, Bangladesh has never allowed the Rohingya to claim asylum. Those who make it to Bangladesh are placed in overcrowded camps without basic provisions, and there they remain unless they choose to return to Myanmar.

The idea of voluntary return stems from a 1993 agreement between Bangladesh and Myanmar, under which those Rohingya who can prove their identity must fill in forms with the names of family members, their previous address in Myanmar, their date of birth, and a disclaimer that they are returning voluntarily. But those who do choose to return will face extortion, arbitrary taxation, and restrictions on freedom of movement. Many will be required to undertake forced labour, and some will face state-sponsored violence and extrajudicial killings.

A refugee camp in Coxsbazar, Bangladesh. EPA/Abir Abdullah

Those who remain in Bangladesh, on the other hand, face a lifetime in camps where human rights abuses are rife, with insufficient and inadequate food, water, housing or healthcare. Fleeing these camps leaves them undocumented and vulnerable to trafficking, exploitation and abuse.

Whatever individual Rohingya people in Bangladesh might decide to do, their future is bleak. And that’s not good enough. The international community has long known about the systematic persecution of this people. The international community has long ignored the atrocities perpetrated against them. And the international community has long tolerated the cover-ups and excuses from the government of Myanmar. This time it needs to be different.

![]() Bangladesh should step up and provide refuge to those who have been seeking it for 25 years. Myanmar’s neighbouring states and allies should help properly resettle the hundreds of thousands of undocumented Rohingya who have fled Myanmar, and Myanmar itself should be held to account for the atrocities it commits. There’s no point saying “never again” unless action is taken.

Bangladesh should step up and provide refuge to those who have been seeking it for 25 years. Myanmar’s neighbouring states and allies should help properly resettle the hundreds of thousands of undocumented Rohingya who have fled Myanmar, and Myanmar itself should be held to account for the atrocities it commits. There’s no point saying “never again” unless action is taken.

Rosa Freedman, Professor of Law, Conflict and Global Development, University of Reading

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.