Offshore Wind Energy: The first offshore wind project was installed off the coast of Denmark in 1991. Since that time, commercial-scale offshore wind facilities have been operating in shallow waters around the world, mostly in Europe. Nysted Wind Facility, 8-12 miles offshore Denmark, the North Sea.

(Credit: National Renewable Energy Laboratory)

Jonathan Buonocore, Harvard University

New plans to build two commercial offshore wind farms near the Massachusetts and Rhode Island coasts have sparked a lot of discussion about the vast potential of this previously untapped source of electricity.

But as an environmental health and climate researcher, I’m intrigued by how this gust of offshore wind power may improve public health. Replacing fossil fuels with wind and solar energy, research shows, can reduce risks of asthma, hospitalizations and heart attacks. In turn, that can save lives.

So my colleagues and I calculated the health impact of generating electricity through offshore wind turbines – which until now the U.S. has barely begun to do.

Greening the grid

New England gets almost none of its electricity from burning coal and more than three-quarters of it from burning natural gas and operating nuclear reactors. The rest is from hydropower and from renewable energy, including wind and solar power and the burning of wood and refuse.

The health benefits of moving to wind power would be significant, particularly for regions that rely more heavily on coal and oil to generate electricity.

Replacing coal and oil with offshore wind will reduce emissions of air pollutants like fine particulate matter, nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide. These pollutants can form smog, soot and ozone. When people downwind are exposed to them, they can develop incapacitating and deadly diseases.

Saving 13 lives a year

When my colleagues and I studied what would happen if offshore wind farms were installed off the Mid-Atlantic coast, we determined that they would bring about health and climate benefits.

We projected that a 1,100-megawatt wind farm off the coast of New Jersey, a bit smaller than the two approved offshore wind farms, would save around 13 lives per year.

When connected to the grid, this new source of power would make carbon emissions decline by around 2.2 million tons every year, the equivalent to taking over 400,000 cars off the road.

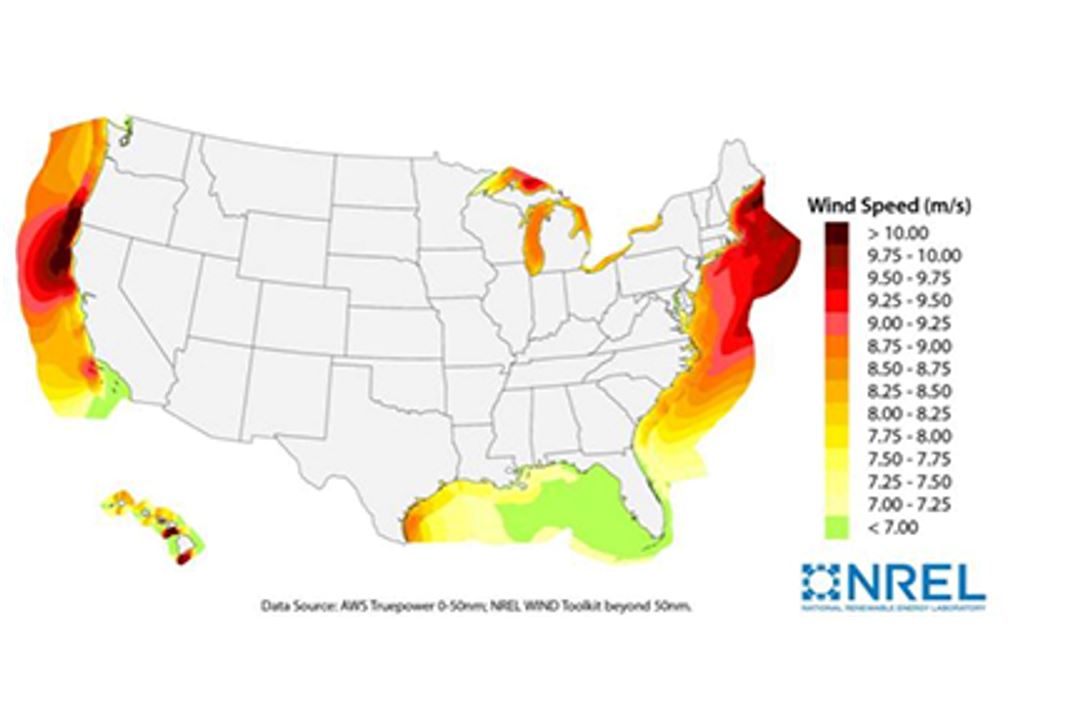

Offshore wind faces a number of technical and economic hurdles, including installation of transmission lines. But at least theoretically, this form of renewable energy could generate enough electricity to supply all the electricity the U.S. consumes and then some, according to the Energy Department. Members of the Trump administration, including Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, appear to support offshore wind.

While it may not be possible, practical or necessary to build offshore wind everywhere, even replacing a small portion of the nation’s fossil-fueled electricity will be good for everyone’s health.![]()

Jonathan Buonocore, Research Associate, Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.