Photo: Håkon Mosvold Larsen / NTB

By David Chelsom Vogt Philosopher and musician

Translated by Bergensia, Originally published in Bergens Tidende

In August, the Conservative Party held a seminar on reducing social and economic disparities, in September they decide to abolish the wealth tax.

Since they hardly see the contradiction themselves, let’s get it in black and white from research teams: “A progressive tax on wealth is a necessary tool if economic inequality is to be reduced.“

This is the conclusion of Thomas Piketty, the French star economist who in his new book has spent 1100 pages examining the historical development of inequality throughout the world. Required, that is. Indispensable. The Conservative Party wants to reduce, and in the long run remove, a form of taxation that history has shown is absolutely necessary to achieve a goal that the Conservatives themselves have advocated.

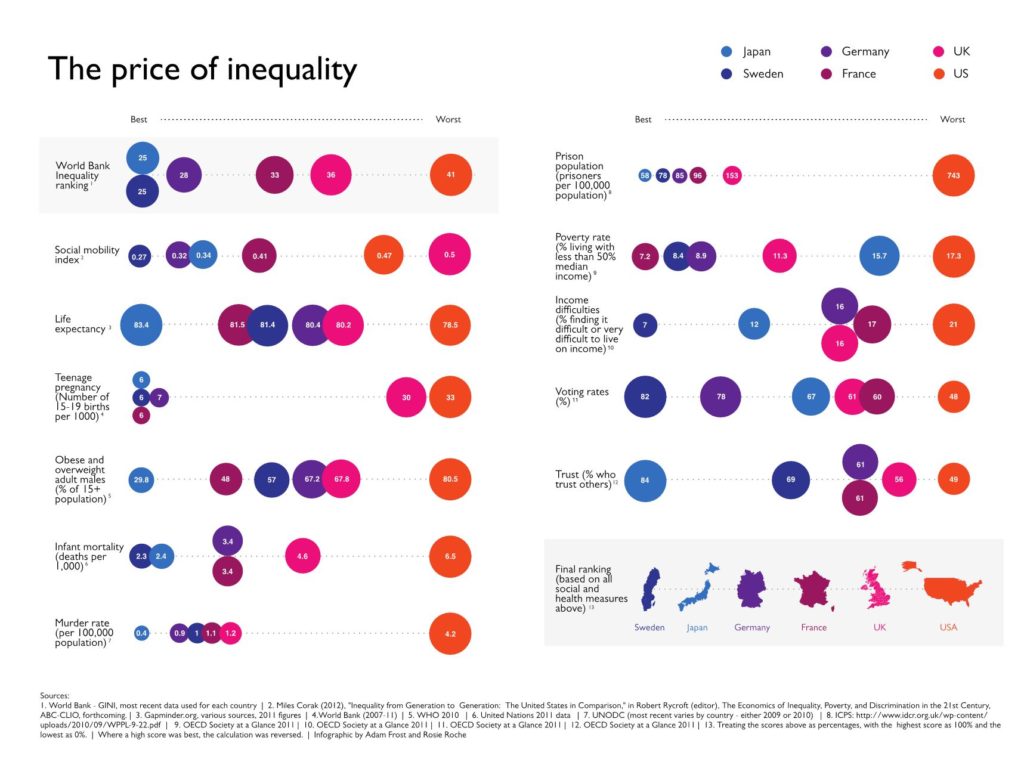

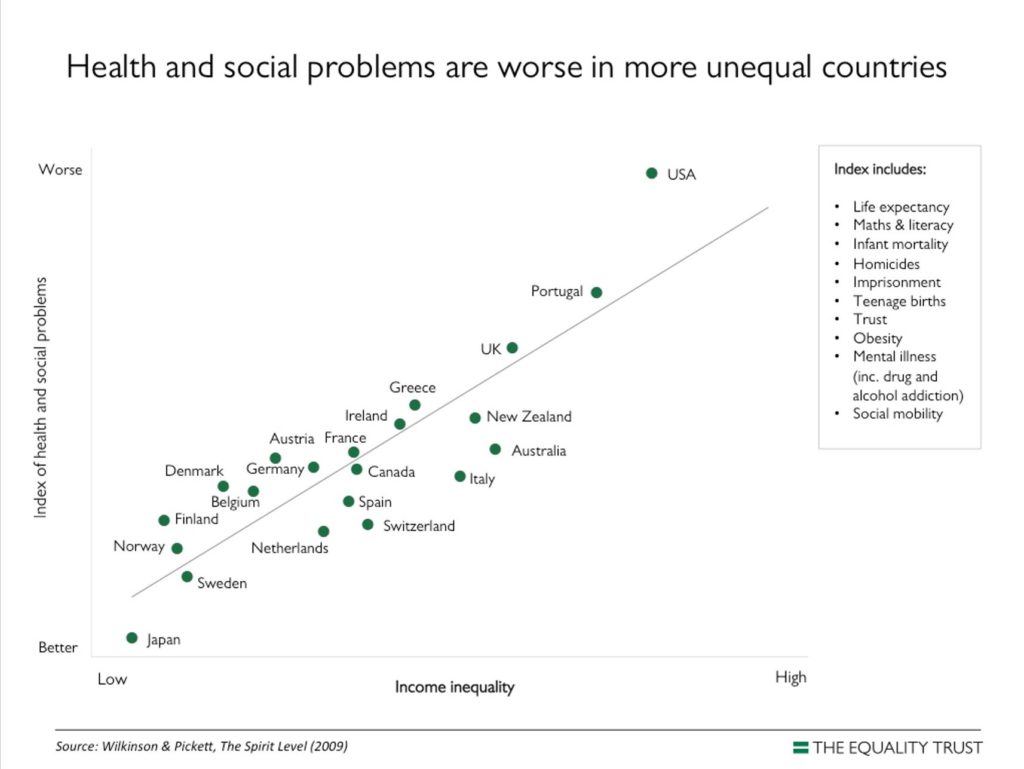

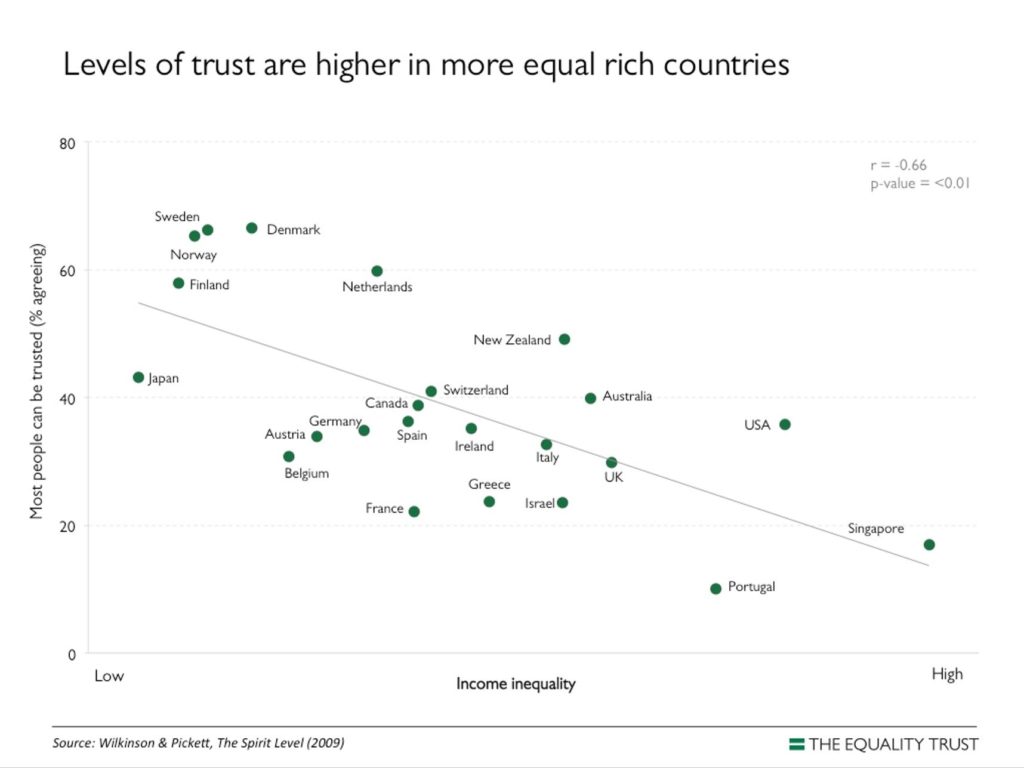

And it is not just any goal: Economic inequality is like poison in a society when it grows big. It causes increased problems with crime, health, intoxication, violence, social mobility, trust – and not least increased polarization in society, which we have unfortunately seen more and more of.

Photo: Vidar Ruud/ NTB

Recent figures from Statistics Norway show that inequality in Norway has grown significantly greater than previously assumed.

Yes, but, we stimulate growth, which benefits the poor, the Conservatives will probably answer. But this “trickle-down” theory is rejected both by the OECD and by an overwhelming majority of economics professors in Norway.

On October 2., a new report was issued by the government itself, but which has a conclusion that the government does not like: Increased wealth tax will create more, not fewer jobs.

Conservative Trond Helleland rejects the new report: “There are many reports on wealth tax”, he says lightly. Yes, it does, but the many reports say the opposite of what the Conservatives want to hear.

How can we explain that a self-proclaimed “knowledge party” has this well-developed ability to ignore the knowledge that is contrary to their adopted tax policy? The answer is ideology. As one vise guy has said, “Ideology is the erroneous notion that one’s perceptions are neither perceptions nor erroneous.” We think we know something, and we do not know that what we think we know is just something we believe.

Everyone has such ideological blind spots; perceptions that overshadow facts. This definitely does not only apply to the Conservatives. But in tax policy, the Conservatives’ blind spots are strikingly large. The reason is an exaggerated belief in what we can call “natural property rights“.

Natural property has its defender in the philosopher John Locke and the idea that one becomes the owner of a thing through making it. If you plow the soil or plant an apple tree, you get a natural right to the fruits of your labor. The theory fits well with Isak Sellanraa from Knut Hamsun’s “Growth of the Soil“, but poorly with a modern business owner. Modern ownership is made possible not only by individual efforts but by social and legal structures. Property rights are conventional, not natural, was Immanuel Kant’s answer to Locke.

When Olav Thon is asked for investment advice, he answers: “Location, location, location“.

Thus, he acknowledges that he has not created his fortune on his own. Thon has not created the public transport and the cultural and school facilities that make the location valuable.

Nor has he made the contract law or the copyright protection or the rent dispute committee and other legal structures that are absolutely necessary for the Thon group to make money. And it is not Thon who has paid for the education of those who work for him.

Why is this important? Because it costs money to create the social and legal structures that make any fortune possible. No tax, no wealth. Just as you have to pay for the materials when you build a house, you have to pay for the legal structures that allow you to own the house.

It, therefore, makes no sense to claim that it is fundamentally wrong to tax wealth, inheritance, and property.

All economic values and transactions that depend on tax to exist can be legitimately taxed. One has no moral right to a fortune without wealth tax.

The interesting question is therefore not whether to tax wealth, inheritance, and property, but how much they should be taxed.

The answer to that question must take into account both what is economically efficient and the fact that the system of property rights – including the tax system – as a whole must create a fair distribution of goods.

In the new book Fair distribution and fair tax, Jørgen Pedersen at HVL analyzes the Norwegian tax system on the basis of the most recognized philosophical theories of justice. Pedersen’s conclusion is clear: “The Norwegian tax system is unfair as it is now because it allows too much capital concentration”.

Today’s tax policy leads to increased social differences, which in turn undermines the goal that the Conservatives have set that “everyone should have equal opportunities regardless of social background”.

When the instruments undermine one’s political goals, a rational approach dictates that the instruments must be changed. Then it remains to be seen whether the Conservatives continue to control tax policy in ideological blindness.