Gary_Ellis_Photography / shutterstock

Tom Oliver, University of Reading

There’s a new nature conservation strategy in town – and it means business. During the 1970s, 80s, and 90s the main tactic to protect wildlife was to highlight the plight of charismatic “flagship” species (remember the WWF Save the Panda campaign?). Since the millennium, however, a new strategy backed by major conservation organisations such as The Nature Conservancy is to price the benefits that nature provides.

Not all conservationists agree, as borne out by fierce debates in a major international initiative assessing global biodiversity. Yet the idea is now mainstream, as evidenced by the high profile Economics of Biodiversity: Dasgupta Review commissioned by the UK government and lead by the economist Partha Dasgupta.

Proponents of the economic approach argue that if we don’t give nature a price then we essentially treat it as having zero value. In contrast, if we articulate the value in monetary terms then this can be factored into government and business decisions. Harmful costs to the natural world are no longer “externalised”, to use the economic jargon, and instead, the value of “natural capital” is incorporated into balance sheets.

There is certainly some merit to this approach, as shown in pilot projects where landowners are paid to improve water quality or reduce flooding. Although it’s worth noting that decisions can go the other way too, as occurred when a major airport and trade zone in Durban, South Africa, got the go-ahead when forecasted jobs and economic growth were deemed to outweigh the economic value of the environment that would be destroyed.

Obviously, not all aspects of nature’s value can be captured in economic terms. Nature is also valued in ways that are spiritual, for example. This is fully recognised by advocates of the approach, who suggest their estimates simply convey minimum values.

The large city of Durban is found in an official ‘biodiversity hotspot’. Slow Walker / shutterstock

On the other side of the debate, concerns about monetary valuation relate to how it might undermine other aspects of nature protection.

To give an example, consider the EU-funded NatureTrade project, in which computer algorithms are used to quantify benefits from nature (such as carbon storage, pollination, recreation) derived on someone’s land. Landowners are then helped to draw up a contract so they can be paid for these, in an auction the researchers behind the project describe it as an “eBay for ecosystem services”. This may seem a great idea, but studies have found that many landowners already protect nature simply because it’s the “right” thing to do, and paying them “crowds out” these social norms.

A hierarchy of needs

Despite the debate, both viewpoints can in fact be complementary.

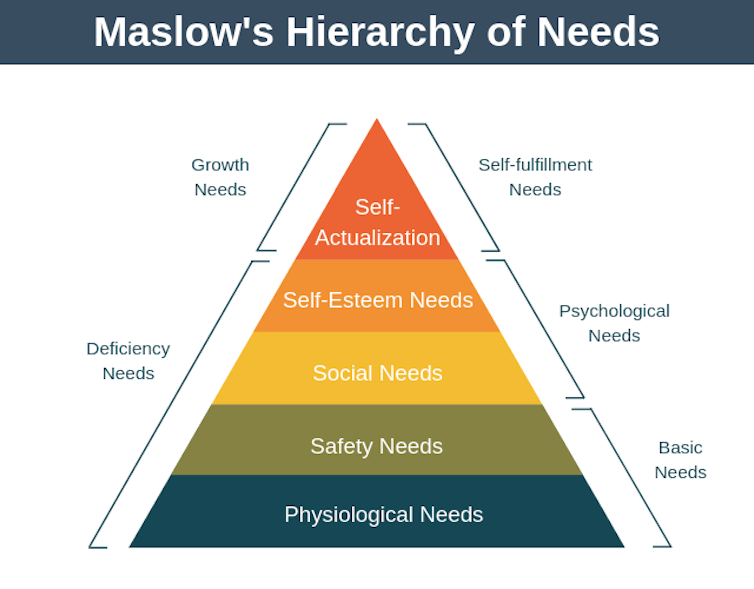

As an analogy, take psychologist Abraham Maslow’s idea of the hierarchy of needs for human development. These are often illustrated as a pyramid, with quantifiable physiological needs and security at the bottom, and the less tangible values of belonging, esteem, and transcendence at the top. A recent book reveals that Maslow intended improvement of all these aspects simultaneously (after all, what use is security and safety if we do not have hope and meaning?).

There is some debate over whether Maslow himself ever represented his theory as a pyramid.

nmilligan / wiki, CC BY-SA

If we were to draw up a similar pyramid representing a healthy environment, at the bottom would be the bare essentials provided by nature, such as having clean air and water, and insects to pollinate crops. Higher up in the pyramid would be the benefits of nature for mental health, and the transcendental aspects which give purpose and spiritual meaning. Different types of people and academic disciplines focus on different layers of the pyramid, but we need them all.

Sometimes the language used by economists doesn’t help. The Dasgupta Review provocatively states: “Nature is an asset.” Yet the boundaries between ourselves and the natural world are more fuzzy than they may first seem, as I evidence in my book The Self Delusion. As Sigmund Freud realised in 1930, when we feel a kinship with – or to use the non-scientific term “love” – something, then we don’t objectify it. Instead, boundaries disappear and it merges with our sense of identity. It is antithetical to many people to refer to a dancing swift, an elegant swan, or friendly-looking robin as an “asset”.

Words matter and there is also danger that such language of commodification can encourage psychological distancing. People who feel less connected to nature do less to protect it. This is why there is a growing movement involving organisations such as the RSPB (the UK’s largest bird charity), to restore a sense of connection to nature, especially in children.

Given the worry that commodification of nature will pollute our worldviews, the big question is whether we can restrict such parlance to domains of policy and business accounting (where it can arguably do some good). I think we can. Consider how human life is valued: in monetary terms by insurance companies and for medicine procurement by health services, yet still in terms of infinite worth to most of us. Just because monetary valuation is used in some sectors doesn’t mean it will flood across to all.

A diversity of viewpoints and approaches is essential to protecting nature effectively. The “economics of nature” is likely here to stay, but that does not replace the tireless efforts of those who have worked for decades to convey the awe-inspiring and transcendental value of nature. As the naturalist, Henry David Thoreau put it: “If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.”![]()

Tom Oliver, Professor of Applied Ecology, University of Reading

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.