Michael Clarke, Australian National University

This past weekend, The New York Times’ China correspondents, Chris Buckley and Austin Ramzy, published an expose of over 400 internal Chinese government documents relating to Beijing’s mass detentions of Uighurs, Kazakhs and other Muslim minorities in the far-western region of Xinjiang.

This trove of documents includes 96 internal speeches by Chinese President and Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping, as well as hundreds of speeches and directives by other CCP officials on the strategies of surveillance and control implemented in the region.

The documents confirm previous analyses by researchers on key aspects of the Chinese government’s so-called “reeducation” system for Uighurs. They also reveal new details on both the timing and rationale for the mass detentions and the extent of opposition within the CCP to this approach.

Most importantly, however, the documents confirm Xi’s high level of personal involvement in driving the campaign of repression in Xinjiang.

What the documents confirm

A number of Xi’s internal speeches confirm previous assessments of the reasons behind the implementation of the government’s mass detention and “reeducation” policies.

It’s clear from the documents that fears of potential connections between violence in Xinjiang and Islamic extremism in neighbouring Afghanistan and the battlefields of Iraq and Syria played a key role in Xi’s call for a “people’s war on terrorism”.

In one speech, for instance, Xi remarks that with the American troop withdrawal from Afghanistan, “terrorist organisations” would be “positioned on the frontiers of Afghanistan and Pakistan” while

East Turkestan terrorists who have received real-war training in Syria and Afghanistan could at any time launch terrorist attacks in Xinjiang.

In this context, a number of high-profile terrorist attacks that have occurred in China in recent years, including a train station attack in Kunming and a bombing at a marketplace in Xinjiang’s capital, Urumqi, appear to have confirmed such fears.

As Xi asserted during a visit to a counterterrorism police unit in Urumqi the same month as the marketplace attack, the party must “unleash” the “tools of dictatorship” and “show absolutely no mercy” in its eradication of “extremists”.

Police investigating the knife attacks at Kunming’s train station in 2014, which left 31 people dead and 140 wounded. Sui Shui/EPA

Police investigating the knife attacks at Kunming’s train station in 2014, which left 31 people dead and 140 wounded. Sui Shui/EPAThe documents also demonstrate that the CCP’s recent tendency to frame both “extremists” and religious believers more broadly through the language of biological contagion or drug addiction comes from the top.

Xi himself states that those “infected” by “extremism” would require “a period of painful, interventionary treatment”, lest they have

their consciences destroyed, lose their humanity and murder without blinking an eye.

This language of paternalistic state intervention is not mere rhetoric, but concretely guides policy on the ground.

Read more:

Despite China’s denials, its treatment of the Uyghurs should be called what it is: cultural genocide

This is evident in one document prepared to assist local officials in the city of Turpan respond to queries by Uighur children of relatives sent to “reeducation” camps.

If officials are asked why those sent to the detention centres cannot return home, for example, they should answer by noting the party would be “irresponsible” to

let a member of your family go home before their illness was cured.

Rather, children should be grateful to the state for the detention of their family members and should

treasure this chance for free education that the party and government has provided to thoroughly eradicate erroneous thinking, and also learn Chinese and job skills.

The Turpan document also confirms the link between “reeducation” and forced labour. It notes family members undergoing “reeducation” can

find a satisfying job in one of the businesses that we’ve brought in or established.

As American researcher Darren Byler has detailed, detainees are often compelled to work as low-skilled labour in factories either directly connected to re-education centres or, upon their “release”, in nearby industrial parks where Chinese companies have been incentivised to relocate.

Key revelations in the reporting

There are several major revelations associated with the documents, as well. Most significant of all, according to the Times, is the fact the documents were leaked

by a member of the Chinese political establishment who requested anonymity and expressed hope that their disclosure would prevent party leaders, including Mr. Xi, from escaping culpability for the mass detentions.

Beyond such a (presumably) high-placed official, the leaked documents and reporting also reveal a greater level of dissent and uncertainty within lower levels of the party than previously understood.

Internal party documents note 12,000 investigations in 2017 alone into party members in Xinjiang for “violations” in the “fight against separatism and extremism”.

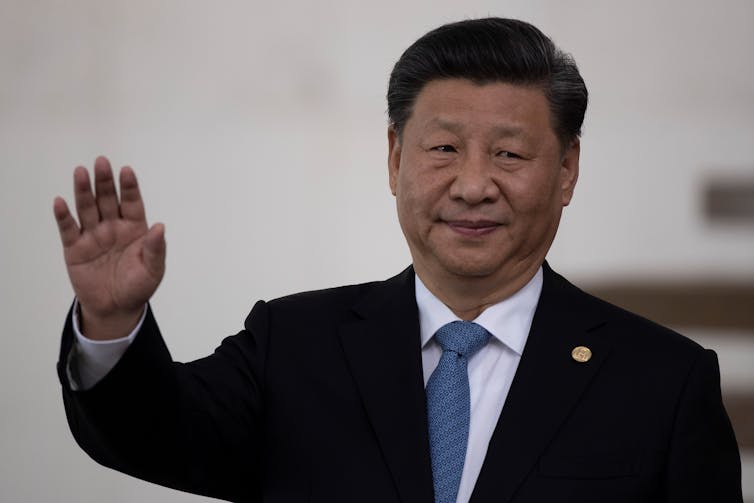

The leaked documents reflect Chinese President Xi Jinping’s personal involvement in driving the campaign of repression in Xinjiang. Andre Coelho/EPA

The leaked documents reflect Chinese President Xi Jinping’s personal involvement in driving the campaign of repression in Xinjiang. Andre Coelho/EPAThe case of CCP official Wang Yongzhi, detailed by Buckley and Ramzy, is indicative here.

According to a “confession”, the local party chief in Yarkand in the far south of Xinjiang initially followed central policy directives by zealously building “two sprawling new detention facilities, including one as big as 50 basketball courts” and “doubling spending on outlays such as checkpoints and surveillance”.

However, fearing mass detentions would negatively impact on economic development goals and social cohesion – key benchmarks for achieving promotion within the party – Wang “broke the rules” and released thousands of detainees.

For this, he was removed from his post in 2017 and in an internal party report six months later was openly castigated for his “brazen defiance” of the “central leadership’s strategy for Xinjiang”.

Read more:

Explainer: who are the Uyghurs and why is the Chinese government detaining them?

Wang’s case demonstrates the existence of competing incentives at the local level in the implementation of centrally dictated policy.

His “brazen defiance” was not a principled stand against mass detentions but rather a pragmatic consideration of the potentially negative effects on his career should detentions undermine broader policy goals.

In this regard, it feels like a fairly typical experience of a low-level official in any authoritarian or totalitarian regime around the world.

It is this mundane quality that gives at least a kernel of hope the naked self-interest of party officials may play a part in pressuring the leadership to eventually reverse course on its Uighur detention policies.

However, given the stark and cold-blooded language revealed in the documents, this may prove to be a forlorn one.![]()

Michael Clarke, Associate Professor, National Security College, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.