Ancient Silk Road – First Global Supply Chain

The Silk Road was approximately 4,000 miles (6,440 km) from its start in China to its end on the shore of the eastern Mediterranean. This compares with 2,440 miles ( 3930 km) between New York and Los Angeles, and 1,760 miles (2,830 km) between Paris and Moscow.

Tom Harper, University of Surrey

As the US begins to enforce what are possibly the strongest sanctions on Iran to date, headlines have been dominated by the bellicose rhetoric of the Trump administration and Tehran. This comes on the heels of Washington’s withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) negotiated by Trump’s predecessor, Barack Obama, alongside Britain, France, Russia, and China.

The marked difference between the latest sanctions and previous rounds has been the criticism of them voiced by European states, who previously had accepted what had been imposed by Washington. So has US unilateralism gone too far?

While the most recent round of sanctions aims to put further pressure on Tehran for regime change and to support American regional allies, such as Israel and Saudi Arabia, they also ha;ve an indirect beneficiary in the form of the US’s biggest global rival, China. And this has wider implications for the region.

The Middle Kingdom meets the Middle East

While European firms have explored ways to circumvent American sanctions or seek waivers, the threat of sanctions is likely to scare away many firms from doing business in the country. This will leave a void that China is likely to fill. As a result, Chinese firms will gain a near monopoly on Iranian oil and trade.

While Chinese imports of Iranian oil have initially experienced a slight decline, it is possible that this is one of Beijing’s ploys to see whether deals serving China’s interests are offered by an increasingly isolated Iran. For while Iran has been receptive to Chinese investment in the past, it has equally sought European investment to balance this out and to prevent China from playing too dominant a role in the country. The sanctions have now made China’s dominance all the more likely.

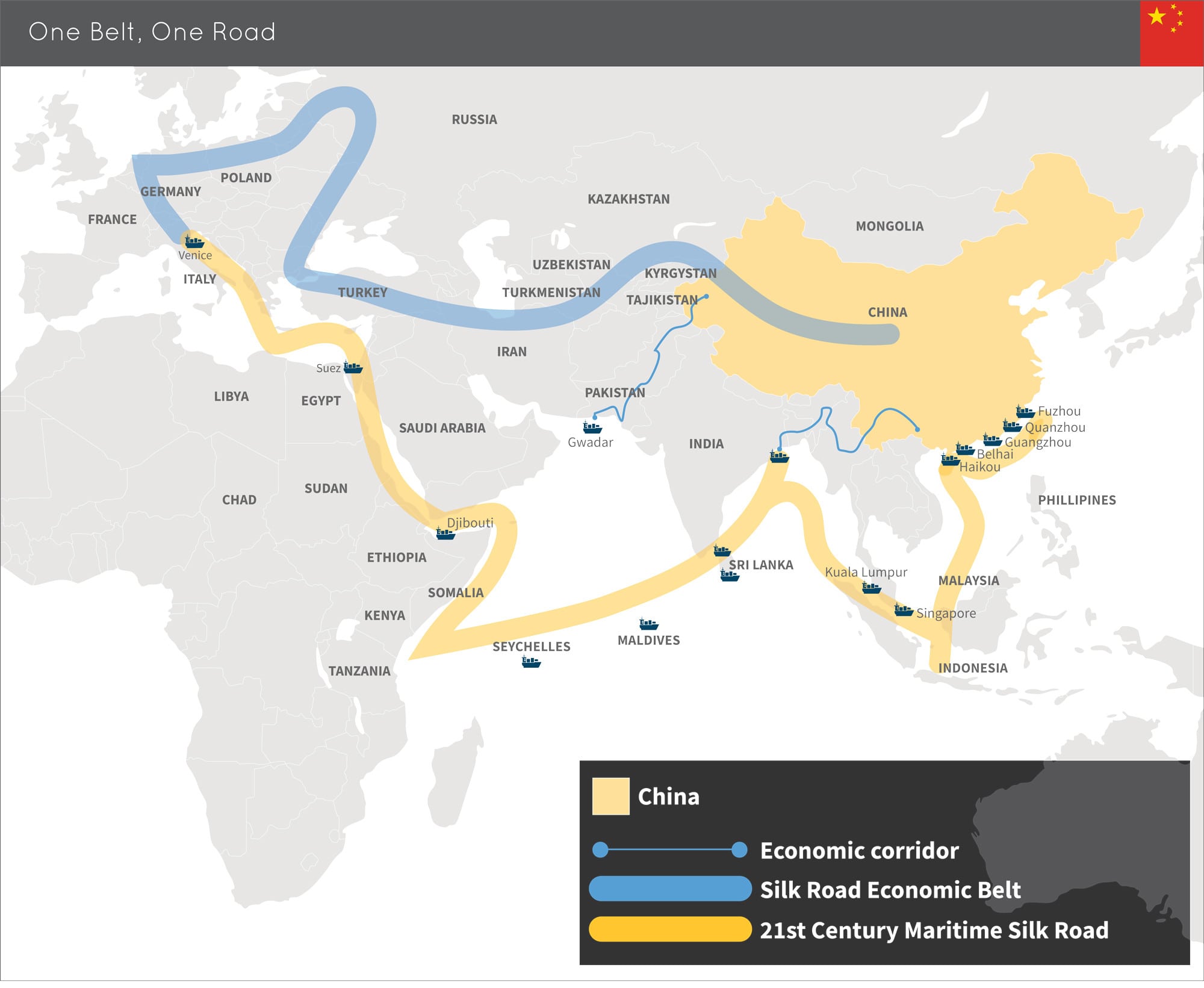

China increasingly is building its influence in a region that has traditionally been dominated by the US. This may see Tehran become more amenable to Chinese global initiatives, such as the Belt and the Road Initiative (BRI) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO).

The former is likely to see further Eurasian integration under China’s watch, while the latter, as a loose military alliance, is likely to be attractive to Iran as a deterrent to regime change.

But while these moves follow the common pattern of Chinese foreign policy, most notably Beijing’s willingness to take greater risks and conduct business in shunned nations, they have wider implications for the region and the wider world.

The way of Mao

Beijing has long been adept at exploiting developments in the international system for its own benefit – and Iran is the latest example of this. In this case, it is filling the void left by European firms that have been scared off by the threat of sanctions.

This raises questions about the utility of sanctions at a time when they have become a cornerstone of the Trump administration’s diplomatic arsenal. While there have been cases of sanctions being successful, most notably in ending apartheid rule in South Africa, they have rarely suceeded in changing state behaviour in recent years.

But possibly the most significant implication is how sanctions have led to widespread de-dollarisation, whereby the dominant global status of the dollar has been challenged. Since sanctioned states are no longer attached to the established system, it is easier for them to adopt an alternative way of operating. An example is the Petro Yuan – whereby China’s oil imports have been priced in yuan rather than in dollars – which has been adopted by oil-rich states targeted by sanctions, most notably Russia and Venezuela. The sanctions on Iran will only exacerbate this process.

Shutterstock

The Petro Yuan is evidence that China is challenging the established US-centric system and seeks to provide an alternative. This is reminiscent of Mao Zedong’s strategies for guerrilla warfare, where an insurgent seeks to make the government irrelevant over a long period of time before overthrowing it. By building ties with sanctioned nations and creating alternative international institutions, China is deploying a similar strategy on a global scale in an effort to bypass the US.

As a result of this, there has also been wider Sino-Russian cooperation, such as in Syria. There, China is poised to play a role in rebuilding the country alongside Russia’s military assistance to it, having found common ground in their concerns over Islamic militancy.

Russia and China were also signatories of the Iran deal and have been dissatisfied with Washington’s abandonment of it. Trump’s present strategies have often been described as a “reverse Nixon”, seeking further ties with Russia to counter China. But the situation in Iran is more likely to see China and Russia jointly challenge the US.

By withdrawing from the deal, Trump has also split the Western world and while it is easy to turn Iran away from the table, it will be tougher to get it back there.

What next?

As a result of these developments, China has become one of the wild cards of the Middle East, challenging and changing the established system there. This also questions the utility of sanctions in the long-term since nations under longstanding sanctions are more open to alternative systems.

By providing an alternative, China seeks to challenge the established system by making it irrelevant. While China has abandoned Mao’s ideology, his strategies continue to be influential.

While the sanctions were seen as an attempt to preserve American dominance in the region, they will have consequences that will indirectly challenge this. This is one US play that could badly misfire.![]()

Tom Harper, Doctoral Researcher in Politics, University of Surrey

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.