Blake Barlow/Unsplash, CC BY

Anda David, Agence française de développement (AFD); Étienne Espagne, Agence française de développement (AFD), and Nicolas Longuet Marx, Agence française de développement (AFD)

From the beginning, the issue of inequality with respect to the impacts of climate change and the global response has been a recurring theme in international climate negotiations. Emerging and developing countries have been sought to spur the developed world into acknowledging its greater burden of responsibility and, accordingly, its obligation to make a larger contribution to the shift toward a low-carbon economy. The concept of climate justice emerged from this debate, inspiring the legal principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” (CBDR).

The CBDR principle is recognised, among others, by the United Nations bodies charged with overseeing the negotiations – hence the effort at COP24 to translate the pledges enshrined in the Paris Agreement into specific, measurable commitments, particularly in relation to the financial transfers between the global North and South. This is the famous “100 billion dollars” a year that developed countries set as their collective target for 2020, with the aim of helping the countries of the Global South take measures to cut emissions and adapt to a changing climate.

Unequal CO2 emissions

The complexity of the relationship between inequality and climate change is also linked to the scope of analysis we choose to adopt. Taking a simple approach, we can identify inequality in terms of carbon emissions on the one hand, and the inequality in terms of impacts on the other. The emissions gap can be measured at multiple levels.

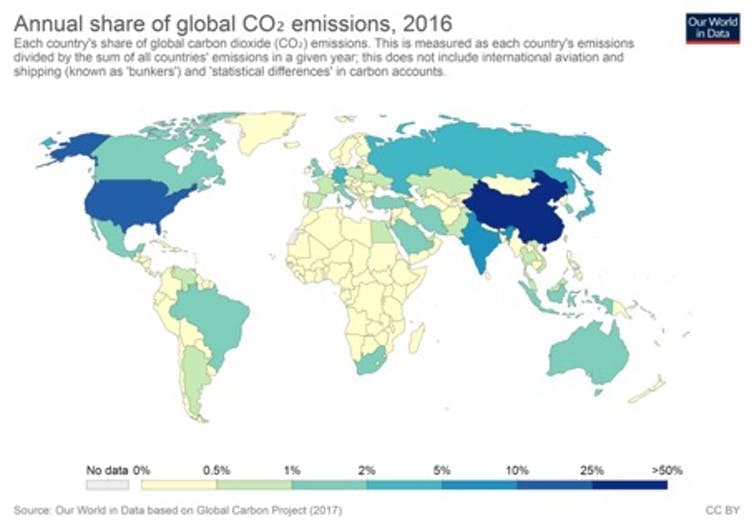

At the country level, China recently became the world’s biggest CO2 emitter, responsible for a startling 26% of global carbon emissions. Africa still has the lowest emissions of any continent, but this masks a great deal of variation between countries, with South Africa by far the largest emitter.

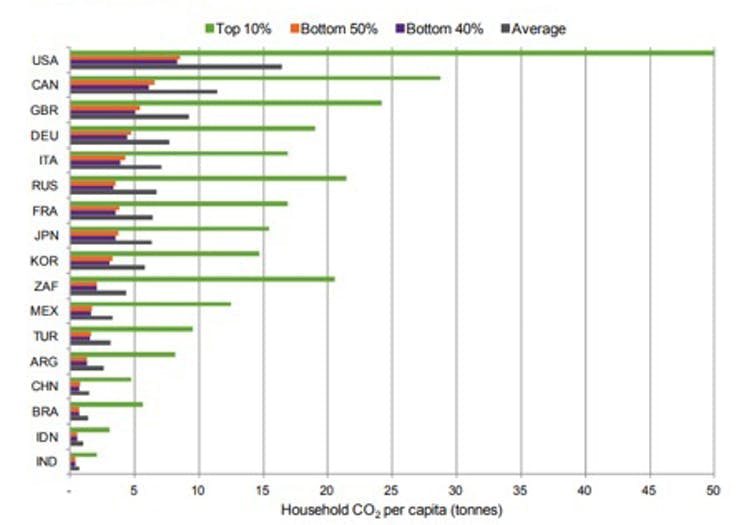

At the individual level, the richest 10% produce around half of all CO2 emissions deriving from consumption, according to a 2015 estimate by <a href=

Our World in Data, Author provided

Oxfam. When we look at per-capita data for the entire globe, the contrasts become even more striking. The Oxfam study also indicates that the lifestyles of the wealthiest Americans are 10 times more emissions-intensive than those of China’s richest.

In the United States, as the share of national income enjoyed by the top 10% grew between 1997 and 2012, there was a corresponding increase in emissions levels. Moreover, inequalities in consumption tend to encourage the formation of carbon-intensive habits: we know that the compulsion to imitate socially prestigious behaviours is one of the key drivers of consumption patterns, and the result of this social mimicry is escalating carbon emissions, as more and more people base their aspirations on the lives of the richest 1%.

Tourism, a quintessentially elitist activity, is now responsible for <a href=

Oxfam, Author provided

almost 8% of global CO2 emissions and the sector’s growth is outpacing all efforts to curtail its impacts. It seems quite clear that highly unequal societies, where economic, cultural, and political power is disproportionately held by the rich, tend to incubate conditions that foreshadow a dangerously carbon-intensive future.

Meanwhile, other mechanisms are also at work. Inequality erodes social cohesion and undermines individual willingness to engage in collective action. It weakens the sense of social responsibility that is so vital to foster demand for pro-environmental policies, as we are seeing at the moment with the climate protests taking place across Europe.

From a technological perspective, economists Francesco Vona and Fabrizio Patriarca have demonstrated how high inequality hampers the development and adoption of new green technologies, as such innovations are accessible to fewer people. Similarly, Lucas Chancel and Thomas Piketty have proposed a consumption-based emissions inequality index to measure differences between income deciles within each country – thus shifting the focus from the national to the individual level. They argue that in a globalised economy it makes more sense to consider the quantity of emissions “consumed” (through the products we buy and the services we use) than to talk about emissions “produced”.

When we adopt this consumption-based approach, the map of emissions inequality reveals some arresting contrasts. A clear gap emerges between the North and South, but also between the world’s wealthiest 10% and everybody else.

Unequal exposure to climatic hazards

Differing degrees of vulnerability to the impacts of climate change are strongly correlated with existing patterns of income inequality. Individual and societal exposure to the hazards of a warming climate varies widely, not only between developed and developing countries (a gap we have known about for a long time), but also between different groups within a country.

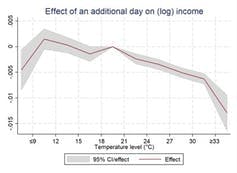

De Laubier el al. (2019), Author provided

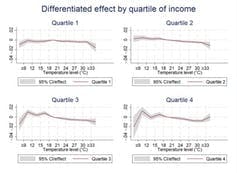

De Laubier el al. (2019), Author provided

In the United States, for example, the effects of climate change are disproportionately felt by the least privileged, and so climate becomes another conduit for reinforcing existing inequalities.

A similar but much more pronounced effect can be observed in an emerging country like Vietnam, which is doubly vulnerable due to its high proportion of agricultural employment and elevated susceptibility to the hazards of climate change. We have demonstrated this in the larger context of a project carried out by the French Development Agency (AFD), GEMMES Vietnam, which presents a systematic analysis of the “socio-economic impacts of climate change and adaptation strategies in Vietnam.”

We found that one additional day per year where the temperature exceeds 33 °C seems to have a strong adverse effect on both the technical efficiency of rice cultivation and household income, widening the gap between income quartiles (the population having been divided into four income groups) irrespective of occupation. This highlights that exposure to climatic hazards is unequal.

Beboy/Shutterstock, CC BY-NC-ND

Climate change not only increases the exposure of the most vulnerable to the ensuing climatic hazards, but it also heightens their sensitivity to its adverse effects and diminishes their capacity to adapt and recover following an extreme climate event.

All indications seem to point to the need to promote more restrained consumption patterns among the wealthy alongside the more general principle of reducing inequalities if we are to have any hope of meeting the objectives set out in the Paris Agreement. Unless we address inequality and curb the excessive emissions generated by the lifestyles of the rich, there is a risk that efforts to live up to the Paris Agreement will lead to a breakdown in the social bond.

In other words, the responsibility to cut carbon emissions must be shouldered by the highest-income countries, and by the most privileged social groups in certain emerging and developing nations. Achieving this goal will require a drastic contraction of consumption habits. The surest path to meeting the COP21 objectives is by tackling inequality and strengthening the social bond – especially if we are to achieve the most ambitious goal of capping the average global temperature rise at just 1.5 °C.![]()

Anda David, Chargée de recherche, Agence française de développement (AFD); Étienne Espagne, Économiste, Agence française de développement (AFD), and Nicolas Longuet Marx, Project Officer for Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, Agence française de développement (AFD)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.