BJP’s government is using both law and violence to target Muslims across India and particularly in Indian occupied Kashmir. More than one international institution documents that the state of human rights in India is deteriorating.

India’s recently passed Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 is a frontal assault on the idea of India as a secular, pluralist democracy.

For the first time, legal sanction has been given to the recasting of India as a Hindu majoritarian nation where minorities, especially Muslims, are second-class citizens. Signed into law after rushed debates in the parliament, the act is a stark regression of the trajectory of India as a mature constitutional democracy. Anil Varughese, Carleton University

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won the May 2019 elections with a majority to return Prime Minister Narendra Modi for a second term. The Modi government continued its widespread practice of harassing and sometimes prosecuting outspoken human rights defenders and journalists for criticizing government officials and policies.

‘Extremely’ concerned by Modi’s anti-Muslim drift: Human Rights Watch #Modi #CAA #India pic.twitter.com/y17vbWyCwC

— SIASAT TV (@thesiasattv) January 15, 2020

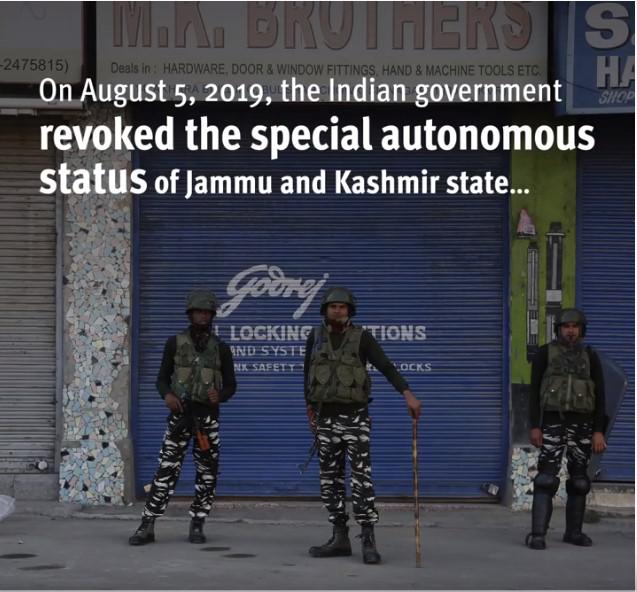

In August, the government revoked the special constitutional status of Jammu and Kashmir and split the province into two separate federally governed territories. Before the announcement, the government deployed additional troops to the province, shut down the internet and phones, and placed thousands of people in preventive detention, prompting international condemnation.

The government failed to properly enforce Supreme Court directives to prevent and investigate mob attacks, often led by BJP supporters, on religious minorities and other vulnerable communities.

Modi’s antidemocratic attitudes have been cultivated through his training. He rose through the ranks of the male-only Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the parent organization of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The RSS was founded in 1925 and is a prominent proponent of “Hindutva — Hindu-ness and the idea that India should be a ‘Hindu nation.’”

In the northeast state of Assam, a citizenship verification project excluded nearly two million people, mostly of Bengali ethnicity, many of them Muslim, putting them at risk of statelessness.

August 26, 2019 Video

India: Ensure Rights Protections in Kashmir

The Indian government should ensure that rights are protected after lifting some restrictions in Jammu and Kashmir State. The government announced that it had partially restored landline connections, reopened schools, and withdrawn the ban on large gatherings. The government imposed the restrictions after it revoked the state’s special autonomous status on August 5, 2019, and split it into two federally governed territories.

Jammu and Kashmir

On February 14, a suicide attack on a security forces convoy in Pulwama district killed over 40 Indian troops. The Pakistan-based militant group Jaish-e-Mohammad claimed responsibility. It led to military escalation between India and Pakistan. Following the attack, Kashmiri students and businessmen in other parts of India were harassed, beaten, and even forcibly evicted from rented housing and dorms by BJP supporters.

On August 5, before revoking the state’s special autonomous status, the government imposed a security lockdown and deployed additional troops. Thousands of Kashmiris were detained without charge, including former chief ministers, political leaders, opposition activists, lawyers, and journalists. The internet and phones were shut down. The government said it was to prevent loss of life, but there were credible, serious allegations of beatings and torture by security forces.

By November, even though some restrictions were lifted, hundreds remained in detention and mobile phone services and internet access was still limited. The government blocked opposition politicians, foreign diplomats, and international journalists from independent visits to Kashmir.

Violent protesters at times threatened those that failed to join shutdowns to counter the government claims that the situation was normal. At least eight people were killed in attacks by militant groups.

Earlier, in July, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights released an update on its 2018 report raising serious concerns about abuses by state security forces and armed groups in both Indian and Pakistani parts of Kashmir and said neither country had taken concrete steps to address concerns that the earlier report raised. The Indian government dismissed the report as a “false and motivated narrative” that ignored “the core issue of cross-border terrorism.”

Impunity for Security Forces

Despite numerous independent recommendations, including by United Nations experts, the government did not review or repeal the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, which gives soldiers effective immunity from prosecution for serious human rights abuses. The law is in force in Kashmir and in several states in northeast India.

In Uttar Pradesh state, police continued to commit extrajudicial killings with impunity. As of June, at least 77 people had been killed and over 1,100 injured since the BJP state government took office in March 2017. In January, four UN rights experts raised concerns over the killings, and over police threats against those pressing for justice in these cases. A petition seeking a court-monitored independent investigation was pending in the Supreme Court at the time of writing.

The killings highlighted a continued lack of accountability for police abuses and the failure to enforce police reforms.

Dalits, Tribal Groups, and Religious Minorities

Mob violence against minorities, especially Muslims, by extremist Hindu groups affiliated with the ruling BJP continued throughout the year, amid rumors that they traded or killed cows for beef. Since May 2015, 50 people have been killed and over 250 people injured in such attacks. Muslims were also beaten and forced to chant Hindu slogans. Police failed to properly investigate the crimes, stalled investigations, ignored procedures, and filed criminal cases against witnesses to harass and intimidate them.

Dalits, formerly “Untouchables,” faced violent attacks and discrimination. In September, the Supreme Court issued notices to authorities to examine caste-based exclusion at universities across India following a petition filed by mothers of two students—one Dalit and one from a tribal community—who committed suicide allegedly due to discrimination.

Nearly 2 million people from tribal communities and forest-dwellers remained at risk of forced displacement and loss of livelihoods after a February Supreme Court ruling to evict all those whose claims under the Forest Rights Act were rejected. Amid concerns over flaws in the claim process, the court stayed the eviction temporarily. In July, three UN human rights experts urged the government to conduct a transparent and independent review of the rejected claims, and evict only after it exhausted all options, ensuring redress and compensation.

Freedom of Expression and Privacy

Authorities used sedition and criminal defamation laws to stifle peaceful dissent. In October, police in Bihar state filed a case of sedition against 49 people, including well-known movie personalities, for writing an open letter to Prime Minister Narendra Modi expressing concerns over hate crimes and mob violence targeting minority communities. Following widespread condemnation, authorities closed the case within days.

Journalists were harassed, even detained, for their reporting or critical comments on social media, and faced increasing pressure to self-censor. In September, police in Uttar Pradesh filed a criminal case against a journalist for exposing mismanagement of the government’s free meal scheme in government schools. In June, police arrested three journalists, accusing them of defaming the Uttar Pradesh state chief minister.

India continued to lead with the largest number of internet shutdowns globally as authorities resorted to blanket shutdowns either to prevent social unrest or to respond to an ongoing law and order problem. By November, there were 85 shutdowns, out of which 55 were in Jammu and Kashmir, according to Software Freedom Law Centre.

In July, the parliament passed amendments to the biometric identification project, Aadhaar Act, paving the way for its use by private parties. The amendments raised concerns over privacy and data protection and were made in the face of a September 2018 Supreme Court ruling restricting the use of Aadhaar for purposes other than to access government benefits and to file taxes.

In December 2018, the government proposed new Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines) Rules that would greatly undermine the rights to freedom of expression and privacy of users.

In October, the social media company WhatsApp, owned by Facebook, confirmed that 121 users in India were targeted by surveillance software owned by NSO, an Israeli firm, out of which at least 22 were human rights activists, journalists, academics, and civil rights lawyers. The government denied purchasing the software.

Civil Society and Freedom of Association

Authorities used the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act (FCRA) to harass outspoken rights groups and restrict their ability to obtain foreign funding. In June, authorities filed a criminal case against Lawyers Collective—a group that provides legal aid, advocates for the rights of marginalized groups, and campaigns to end discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual, and queer (LGBTQ) people. In November, authorities sought the court’s permission to arrest the organization’s founders for custodial interrogation despite their cooperation in the investigation.

Nine prominent human rights activists, imprisoned in 2018 under a key counterterrorism law; the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), remained in jail, accused of being members of a banned Maoist organization and of inciting violent protests. In the same case, in September, authorities conducted a raid on the home of a Delhi University professor who has been vocal on the rights of persons with disabilities and against caste discrimination.

In August, the federal government passed amendments to the UAPA allowing individuals to be designated as terrorists despite concerns by rights groups over how the law already infringes on due process rights and has been misused to target religious minorities, critics of the government, and social activists. The amendments have been challenged in the Supreme Court as unconstitutional and the case was pending at the time of writing.

Refugee and Citizenship Rights

In August, the government in Assam published the National Register of Citizens, aimed at identifying Indian citizens and lawful residents following repeated protests and violence over irregular migration of ethnic Bengalis from Bangladesh. The list excluded nearly two million people, many of them Muslims, including many who have lived in India for years, in some cases their entire lifetimes. There are serious allegations that the verification process was arbitrary and discriminatory, although those excluded from the list have the right to judicial appeal.

The Assam state government said it will build ten detention centers for those denied citizenship after appeal. In September, India’s home minister declared that the National Register of Citizens will be implemented across the country and that the government will amend the citizenship laws to include all irregular migrants from neighboring countries apart from Muslims.

In 2019, the government deported eight Rohingya Muslims to Myanmar, a family of five members in January and a father and his two children in March, after deporting seven people in October 2018. In April, five UN human rights experts condemned the deportations saying they violated international law. They also raised concerns over the indefinite detention of some Rohingya in India.

Women’s Rights

High profile rape cases during the year, including against a BJP leader, highlighted how women seeking justice face significant barriers, including police refusal to register cases, victim blaming, intimidation and violence, and lack of witness protection. The accused leader was arrested in September after widespread condemnation, including on social media.

In April, a sexual harassment complaint against the sitting chief justice of the Supreme Court illustrated similar challenges. Other women who complained against powerful men also became vulnerable to criminal defamation cases.

Children’s Rights

In August, the parliament amended the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act 2012, introducing the capital punishment for aggravated penetrative sexual assault of anyone under 18 years, and increased the penalty for other sexual offenses. This was despite concerns raised by child rights groups that it could lead to a decrease in police complaints because in nearly 95 percent of reported cases, the perpetrator is known to the victim, in positions of authority, or family members.

In November, following a petition by child rights activists, the Supreme Court sought a detailed report from the juvenile justice committee of the Jammu and Kashmir High Court on the alleged detention of children and other abuses during the lockdown imposed since August. The committee earlier submitted a police list of 144 detained children, the youngest being 9. Most, police said, were released, after warnings against participating in violent protests.

Disability Rights

Girls and women with disabilities continue to be at a heightened risk of abuse and face serious barriers in the justice system, despite legal provisions to safeguard their rights.

Thousands of people with psychosocial or intellectual disabilities languish in residential institutions, where they face overcrowding, lack of hygiene, and physical, verbal, and even sexual violence. Some people with psychosocial disabilities are even shackled—chained or locked up in small confined spaces—due to stigma associated with mental health conditions and lack of appropriate community-based support services.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

The parliament passed the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill. Rights groups criticized the law for failing to provide full protection and recognition to transgender people. The law is unclear on a transgender person’s right to self-identify, which India’s Supreme Court recognized in a landmark judgment in 2014. Its provisions are also contrary to international standards for legal gender recognition.

Key International Actors

The US Congress held two hearings that largely focused on Kashmir. Several lawmakers criticized India’s actions in Kashmir, including political detentions and communications blockade, and raised concerns over other abuses including the citizenship verification process in Assam.

In August, the UN Security Council held a closed meeting on Jammu and Kashmir for the first time in decades. China, which called the meeting at Pakistan’s behest, said members were concerned about human rights and increasing India-Pakistan tensions. US President Donald Trump offered to mediate and resolve the dispute.

In September, the European Union raised the situation in Jammu and Kashmir at the UN Human Rights Council, encouraging India to lift remaining restrictions and to maintain the rights and fundamental freedoms of the affected population. The European Parliament also held a special debate on Kashmir, urging both India and Pakistan to respect their international human rights obligations.

Throughout the year, the UN special procedures issued several statements raising concerns over a slew of issues in India including extrajudicial killings, potential statelessness of millions in Assam, possible eviction of tribal communities and forest-dwellers, and communications blackout in Kashmir. In September, the UN Human Rights High Commissioner Michelle Bachelet expressed concerns over rights violations in Jammu and Kashmir.

Foreign Policy

Relations with Pakistan continued to deteriorate over the year. A militant attack in February targeting a security forces convoy in Kashmir led to retaliatory airstrikes. In August, after India’s decision to revoke special status for Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan downgraded its diplomatic relations and expelled the Indian high commissioner. Pakistan, backed by China and several members of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, also delivered a statement on rights violations in Kashmir at the UN Human Rights Council session in September. Despite a downward spiral in relations, in November, the two countries opened a visa-free border crossing for Indian pilgrims to visit a Sikh shrine in Pakistan.

India did not raise rights protections publicly during bilateral engagements with other neighbors including Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Afghanistan. In August, India’s foreign minister, during his visit to Bangladesh, expressed willingness to provide more assistance to displaced Rohingya in Bangladesh and toward development in Rakhine state in Myanmar. In response to concerns regarding the deportation of nearly 2 million people excluded from the citizenship verification project in Assam, the foreign minister told Bangladesh that it was India’s internal matter.

In a sign of growing ties with the United Arab Emirates, Prime Minister Modi was awarded the country’s highest civilian honor by the crown prince during his visit in August. India faced questions from a UN body and international rights groups for its alleged role in March 2018 for intercepting and deporting the 32-year-old daughter of the Dubai ruler who was trying to flee what she said were restrictions imposed by her family.

In July, India maintained its past position and abstained from voting at the UN Human Rights Council including on the renewal of the mandate for an independent expert on protecting LGBT people from violence and discrimination.