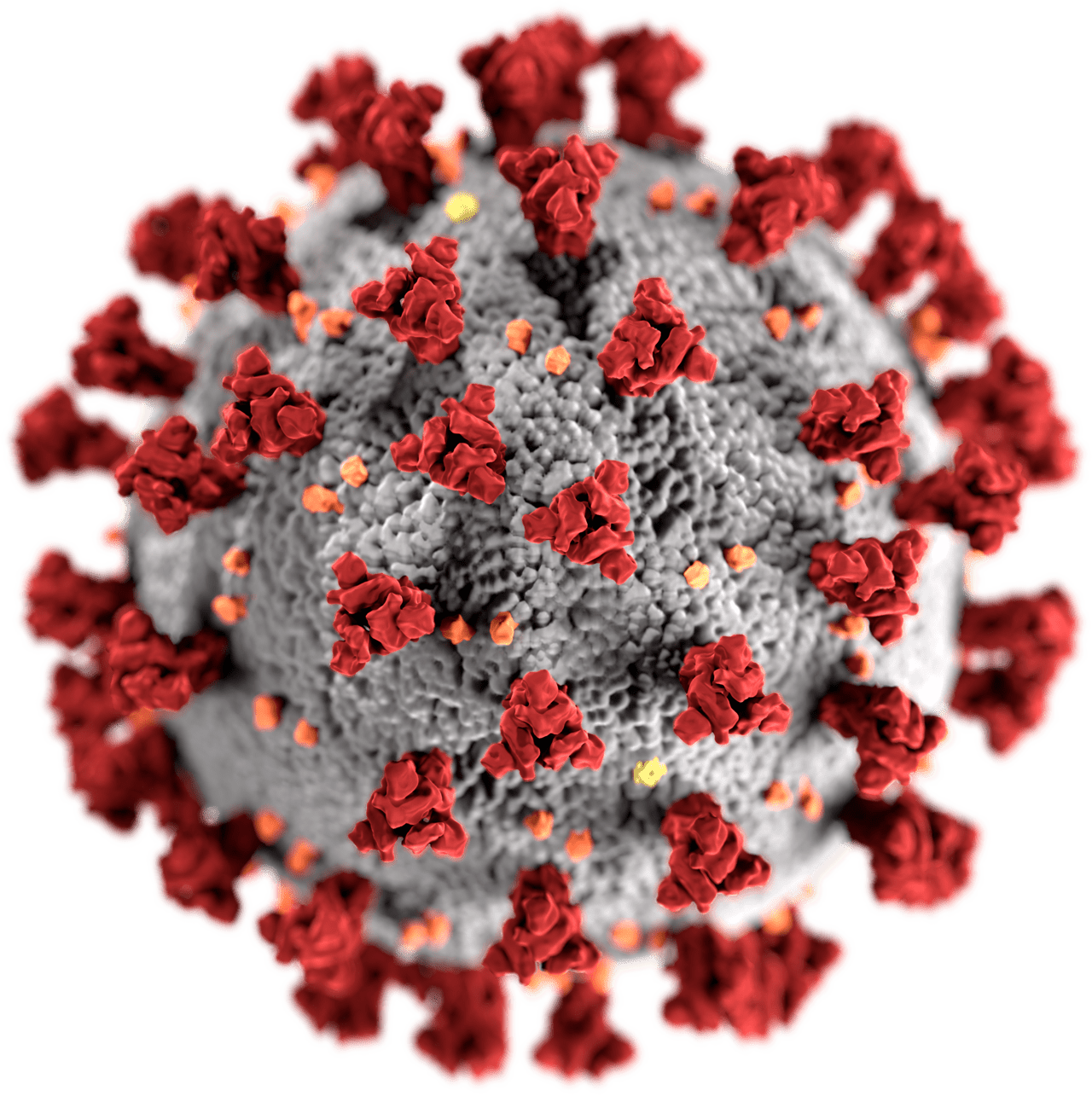

This illustration, created at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), reveals ultrastructural morphology exhibited by coronaviruses. Note the spikes that adorn the outer surface of the virus, which imparts the look of a corona surrounding the virion, when viewed electron microscopically. A novel coronavirus, named Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was identified as the cause of an outbreak of respiratory illness first detected in Wuhan, China in 2019. The illness caused by this virus has been named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). By CDC/ Alissa Eckert, MS; Dan Higgins, MAM #23312.

Measures such as social distancing and stay-at-home orders reduce and delay the peak of active cases, allowing more time for healthcare capacity to increase and better cope with patient load.[1] Time gained through thus flattening the curve can be used to raise the line of healthcare capacity to better meet surging demand.[2] By RCraig09 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

Flattening the curve is a public health strategy introduced during the 2019–20 COVID-19 pandemic. The curve being flattened is the epidemic curve, a visual representation of the number of infected people needing health care over time. During an epidemic, a health care system can break down when the number of people infected exceeds the capability of the health care system to take care of them. Flattening the curve means slowing the spread of the epidemic so that the peak number of people requiring care at a time is reduced, and the health care system is not overwhelmed. Flattening the curve relies on mitigation techniques such as social distancing.

By reducing the probability that a given uninfected person will come into physical contact with an infected person, the disease transmission can be suppressed, resulting in fewer deaths.[1][4] The measures are combined with good respiratory hygiene and hand washing.[7][8]

By Toby Morris (Spinoff.co.nz), CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

A complementary measure is to increase health care capacity, to “raise the line”.[3] As described in an article in The Nation, “preventing a health care system from being overwhelmed requires a society to do two things: ‘flatten the curve’—that is, slow the rate of infection so there aren’t too many cases that need hospitalization at one time—and ‘raise the line’—that is, boost the hospital system’s capacity to treat large numbers of patients.”[4] As of April 2020, in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, two key measures are to increase the number of available ICU beds and ventilators, which are in systemic shortage.[2]

We were all warned about the risk of pandemics

Warnings about the risk of pandemics were repeatedly made throughout the 2000s and the 2010s by major international organizations including the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Bank, especially after the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak.[5] Governments, including those in the United States and France, both prior to the 2009 swine flu pandemic, and during the decade following the pandemic, both strengthened their health care capacities and then weakened them.[6][7] At the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, health care systems in many countries were functioning near their maximum capacities.[3][better source needed] In a situation like this, when a sizable new epidemic emerges, a portion of infected and symptomatic patients create an increase in the demand for health care that has only been predicted statistically, without the start date of the epidemic nor the infectivity and lethality known in advance.[3] If the demand surpasses the capacity line in the infections per day curve, then the existing health facilities cannot fully handle the patients, resulting in higher death rates than if preparations had been made.[3]

An influential UK study showed that an unmitigated COVID-19 response in the UK could have required up to 46 times the number of available ICU beds.[8] The public health management challenge is to keep the epidemic wave of incoming patients needing material and human health care resources supplied in a sufficient amount that is considered medically justified.[3]

Flattening the curve has Life-saving impact

It is often claimed that “flattening the curve” does not lead to a reduction in the total number of individuals infected during the course of the disease; rather, the infections would only spread over a longer period of time. This is not correct if e. g. the SIR model can be applied to the infection.

SIR model showing the impact of reducing the infection rate (orange) by 76 %By Phrontis – own image, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

If it’s possible to prevent infections extremely effectively, a significant number of individuals can actually be protected from being infected.

Non-pharmaceutical interventions such as hand washing, social distancing, isolation, and disinfection[3] reduce the daily infections, therefore flattening the epidemic curve. A successfully flattened curve spreads health care needs over time and the peak of hospitalizations under the health care capacity line.[2] Doing so, resources, be it material or human, are not exhausted and lacking. In hospitals, it for medical staff to use the proper protective equipment and procedures, but also to separate contaminated patients and exposed workers from other populations to avoid intra-hospital spread.[3]

Raising the line

Along with the efforts to flatten the curve is the need for a parallel effort to “raise the line” to increase the capacity of the health care system.[2] Health care capacity can be raised by raising equipment, staff, providing telemedicine, home care, and health education to the public.[3] Elective procedures can be canceled to free equipment and staff.[3]

According to Vox, in order to move away from social distancing and return to normal, the US [or any society] needs to flatten the curve by isolation and mass testing and to raise the line.[10] Vox encourages building up health care capability including mass testing, software, and infrastructures to trace and quarantine infected people, and scaling up cares including by resolving shortages in personal protection equipment, face masks.[10]

References

- Wiles, Siouxsie (2020-03-09). “The three phases of Covid-19—and how we can make it manageable”. The Spinoff. Morningside, Auckland, New Zealand. Archived from the original on 2020-03-27. Retrieved 2020-03-09.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Barclay, Eliza (2020-04-07). “Chart: The US doesn’t just need to flatten the curve. It needs to “raise the line.””. Vox. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i Osmosis.org; Lifebridge Health. Beating Coronavirus: Flattening the Curve, Raising the Line(YouTube video). Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gelardi, Chris (2020-04-09). “Colonialism Made Puerto Rico Vulnerable to Coronavirus Catastrophe”. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ “Wanted: world leaders to answer the coronavirus pandemic alarm”. South China Morning Post. 31 March 2020. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Manjoo, Farhad (25 March 2020). “Opinion | How the World’s Richest Country Ran Out of a 75-Cent Face Mask”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ “Pénurie de masques : une responsabilité partagée par les gouvernements” [Lack of masks: a responsibility shared by governments]. Public Senat (in French). 23 March 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-04-09. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team (16 March 2020). “Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ Roberts, Siobhan (2020-03-27). “Flattening the Coronavirus Curve”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Lopez, German (2020-04-10). “Why America is still failing on coronavirus testing”. Vox. Retrieved 2020-04-12.