Lightspring via Shutterstock

The UK government recently announced a new plan to regulate social media companies such as YouTube, Facebook and Twitter. The proposals give the government’s media regulator, Ofcom, extensive powers to tell tech giants what speech they must suppress – and to punish them if they don’t.

These proposals seem long overdue. Just consider the case of YouTube. Once celebrated for its videos of wedding engagements, graduation speeches and cute cats, its darker corners have been used to display televised beheadings, white supremacist rallies and terrorist incitement. Facebook and Twitter have been similarly abused for nefarious ends.

Surely, the argument goes, it is fitting and proper to hold profiteering social media firms partly accountable for the harms caused by the content they platform. Simply relying on these firms to self-regulate is not enough.

But unless the government’s proposals are dramatically revised, they pose a significant risk to two fundamental political values: freedom of speech and democracy.

Start with the risks to free speech. The current proposal stems from an Online Harms White Paper published in April 2019, which unhelpfully outlines two kinds of speech to be regulated: “harms with a clear definition” and “harms with a less clear definition”.

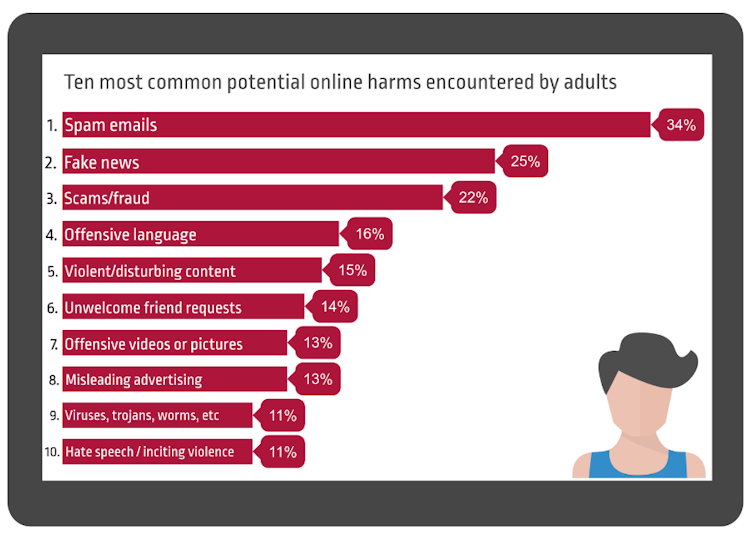

Ofcom: ten biggest online harms in UK.

Ofcom: ten biggest online harms in UK.The former category focuses on speech that is mostly already illegal – offline and online. So, for example, extreme pornography (for example, videos depicting rape) and speech which incites terrorism fall into this category. Yet the second category is nebulous precisely because it concerns speech that is mostly already legal – such as so-called “trolling”, “disinformation” and other “extremist content” (though the white paper offers few examples).

Under the proposal, social media companies will be tasked with a “duty of care” requiring it to restrict the distribution of both kinds of content – with Ofcom to serve as judge, jury and executioner.

Rule of law

It is the second, more nebulous category that should trouble the defenders of free speech. If it is perfectly legal to post certain speech online – if there is good reason to permit citizens to engage in, and access, certain expression without fear of penalty – why should such speech then be subject to suppression (whether in the form of outright censorship or reduced dissemination)?

There may be rare cases in which an asymmetry can be justified – for example, we wouldn’t want to punish troubled teenagers posting videos of their own self-harm, even though we would want to limit the circulation of these videos. But with respect to content propounded by accountable adults – the majority of the speech at issue here – symmetry should be the norm.

If certain speech is rightly protected by the law – if we have decided that adults should be free to express and access it – we cannot then demand that social media companies suppress it. Otherwise we are simply restricting free speech through the backdoor.

For example, take the category of “extremist content” – content judged to be harmful despite it being legal. Suppose Ofcom were to follow the definition used in the government’s Prevent strategy, whereby speech critical of “British values” – such as democracy – counts as extremist. Would social media companies be violating their duty of care, then, if they failed to limit distribution of philosophical arguments challenging the wisdom of democratic rule? We would hope not. But based on what we know now, it’s simply up to Ofcom to decide.

Recent reporting suggests that, with regard to legal speech, the final proposal may simply insist that social media companies enforce their own terms and conditions. But this passes the hard choices to the private companies, and indeed simply incentivises them to write extremely lax terms.

A job for democracy

This leads to my final concern, with democracy. As a society, we have hard choices to make about the limits of freedom of expression. There is reasonable disagreement about this issue, with different democracies taking different stands. Hate speech, for example, is illegal in Britain but broadly legal in the US. Likewise, speech advocating terrorism is a crime in Britain, but is legal in the US so long as it doesn’t pose a high risk of causing imminent violence.

It is instructive that these decisions have been made in the US by its Supreme Court, which gets the final say on what counts as protected speech. But in Britain, the rules are different: the legislature, not the judiciary, decides.

The decision to restrict harmful expression requires us to judge what speech is of sufficiently “low value” to society that its suppression is acceptable. It requires a moral judgement that must carry legitimacy for all over whom it is enforced. This is a job for democracy. It is not a job for Ofcom. If the UK decides that some speech that is presently legal is sufficiently harmful that the power of the state should be used to suppress it, parliament must specify with precision what exactly this comprises, rather than leaving it to be worked out later by Ofcom regulators.

Parliament could do this, most obviously, by enacting criminal statutes banning whatever speech it desires Ofcom to suppress (incorporating the relevant loopholes to protect children and other vulnerable speakers from prosecution). On this model, social media companies would be tasked with suppressing precisely specified speech that is independently illegal, and no more. If the government is not prepared to criminalise certain speech, then it should not be prepared to punish social media companies for giving it a platform.

The government is right to hold social media firms accountable. A duty of care model could still work. But to protect free speech, and ensure that decisions of the greatest consequence have legitimacy, the fundamental rules – about what speech may be suppressed – must be clearly specified, and authorised, by the people. That’s what parliament is for.![]()

Jeffrey Howard, Associate Professor of Political Theory, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.