Bafta Awards 2020: Joaquin Phoenix praised for calling out ‘systemic racism’ in the film industry in his best actor award speech.

Mary Frances O’Dowd, CQUniversity Australia

At the 2020 BAFTA awards, Joaquin Phoenix called out systemic racism in the film industry in his acceptance speech for leading actor.

He said:

I think that we send a very clear message to people of colour that you’re not welcome here. I think that’s the message that we’re sending to people that have contributed so much to our medium and our industry and in ways that we benefit from. […]

I think it’s more than just having sets that are multicultural. We have to do really the hard work to truly understand systemic racism.

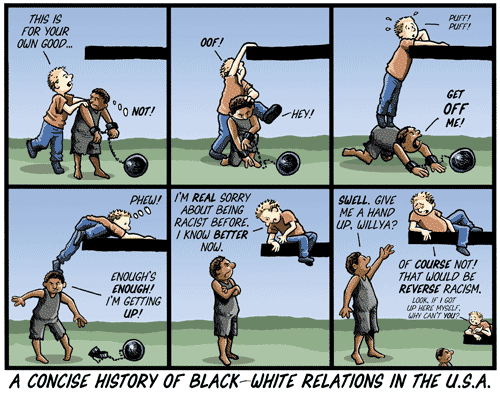

“Interpersonal racism”; When a white person can take their misinformation and stereotypes towards another group and perform an act of harassment, exclusion, marginalization, discrimination, hate or violence they are committing an act of interpersonal racism towards an individual or group.

“Systemic racism”, or “institutional racism”, refers to how ideas of white superiority are captured in everyday thinking at a systems level: taking in the big picture of how society operates, rather than looking at one-on-one interactions.

These systems can include laws and regulations, but also unquestioned social systems. Systemic racism can stem from education, hiring practices or access.

Read more:

Explainer: what is casual racism?

In the case of Phoenix at the BAFTAs, he isn’t calling out the racist actions of individuals, but rather the way white is considered the default at every level of the film industry.

Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton first wrote about the concept in their 1967 book Black Power: The Politics of Liberation.

They wrote:

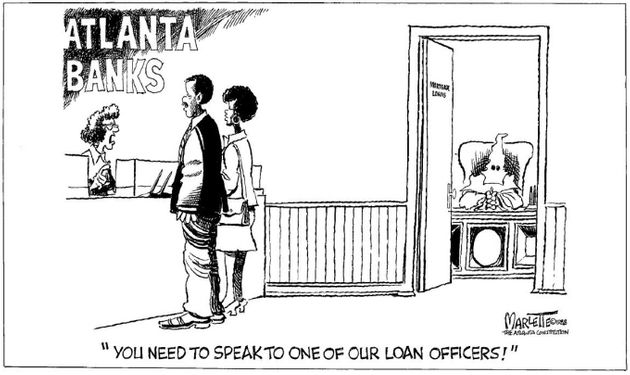

When a black family moves into a home in a white neighborhood and is stoned, burned or routed out, they are victims of an overt act of individual racism which most people will condemn. But it is institutional racism that keeps black people locked in dilapidated slum tenements, subject to the daily prey of exploitative slumlords, merchants, loan sharks and discriminatory real estate agents. The society either pretends it does not know of this latter situation, or is in fact incapable of doing anything meaningful about it.

Invisible systems

Systemic racism assumes white superiority individually, ideologically and institutionally. The assumption of superiority can pervade thinking consciously and unconsciously.

One most obvious example is apartheid, but even with anti-discrimination laws, systemic racism continues.

Individuals may not see themselves as racist, but they can still benefit from systems that privilege white faces and voices.

Anti-racism activist Peggy McIntosh popularised the understanding of the systemic nature of racism with her famous “invisible knapsack” quiz looking at white privilege.

The quiz asks you to count how many statements you agree with, for items such as:

- I can turn on the television or open to the front page of the paper and see people of my race widely represented

- I can be pretty sure of having my voice heard in a group in which I am the only member of my race

- I can worry about racism without being seen as self-interested or self-seeking.

The statements highlight taken-for-granted privileges, and enable people to understand how people of colour may experience society differently.

Cultures of discrimination

Under systemic racism, systems of education, government and the media celebrate and reward some cultures over others.

In employment, names can influence employment opportunities. A Harvard study found job candidates were more likely to get an interview when they “whitened” their name.

Only 10% of black candidates got interview offers when their race could be implied by their resume, but 25% got offers when their resumes were whitened. And 21% of Asian candidates got interview offers with whitened resumes, up from 11.5%.

Systemic racism shows itself in who is disproportionately impacted by our justice system. In Australia, Indigenous people make up 2% of the Australian population, but 28% of the adult prison population.

Joel Carrett/AAP

Read more:

As Indigenous incarceration rates keep rising, justice reinvestment offers a solution

A study into how systemic racism impacts this over-representation in Victoria named factors such as over-policing in Aboriginal communities, the financial hardship of bail, and increased rates of drug and alcohol use.

Australia’s literature, theatres and art galleries are all disproportionately white, with less than 10% of artistic directors from culturally diverse backgrounds.

Read more:

Australia’s art institutions don’t reflect our diversity: it’s time to change that

A way forward

Systemic racism damages lives, restricting access and capacity for contribution.

It damages the ethical society we aspire to create.

When white people scoop all the awards, it reinforces a message that other cultures are just not quite good enough.

Public advocacy is critical. Speaking up is essential.

Racism is more than an individual issue. When systemic injustices remain unspoken or accepted, an unethical white privilege is fostered. When individuals and groups point out systemic injustices and inequities, the dominant culture is made accountable.

Find out if your children’s school curriculum engages with Indigenous and multicultural perspectives. Question if your university course on Australian literature omits Aboriginal authors. Watch films and read books by artists who don’t look like you.

As Phoenix put it in his speech:

I’m part of the problem. […] I think it is the obligation of the people that have created and perpetuate and benefit from a system of oppression to be the ones that dismantle it. That’s on us.

Understanding systemic racism is important. To identify these systemic privileges enables us to embrace the point of view of people whose cultures are silenced or minimised.

When we question systemic racism, worth is shared and ideas grow.![]()

Mary Frances O’Dowd, Senior Lecturer, Indigenous Studies, CQUniversity Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.