More than 10.000 people took part in about 50 paddle-out protests all around the country, from Perth to Townsville, including Bondi, Manly, Gold Coast, Torquay, Byron Bay, Tasmania, and South Australia. Earlier this year thousands joined paddle-out protests around Australia and even in Equinor’s home waters of Oslo. DAN HIMBRECHTS/AAP

Madeline Taylor, University of Sydney and Tina Soliman Hunter

This week’s decision by Norwegian company Equinor to abandon a A$200 million plan to drill for oil in the Great Australian Bight surprised both its critics and backers.

Equinor says it abandoned the project off the remote South Australian coast because it was not “commercially competitive”.

But the plan was flawed from its inception. It was out of step with the investment community’s reduced appetite for frontier fossil fuel exploration, and growing concern about financial exposure to carbon risk. A broad section of the community opposed it on environmental grounds, including the potential for a possibly catastrophic oil spill.

Equinor is the third major oil company to abandon plans to drill in the bight, following BP and Chevron. But the company will remain active in Australia, pointing to an offshore exploration permit off Western Australia. There is also speculation that another company may take over its permit in the bight.

Equinor’s decision is an important win for many Australians, but we cannot rest on our laurels. Reform of Australia’s offshore petroleum laws is urgently required to permanently protect our precious marine environment.

A risky endeavour

In May last year, a group of multi-disciplinary experts, including the authors of this article, made a submission to the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (NOPSEMA), highlighting the risks inherent in Equinor’s proposal.

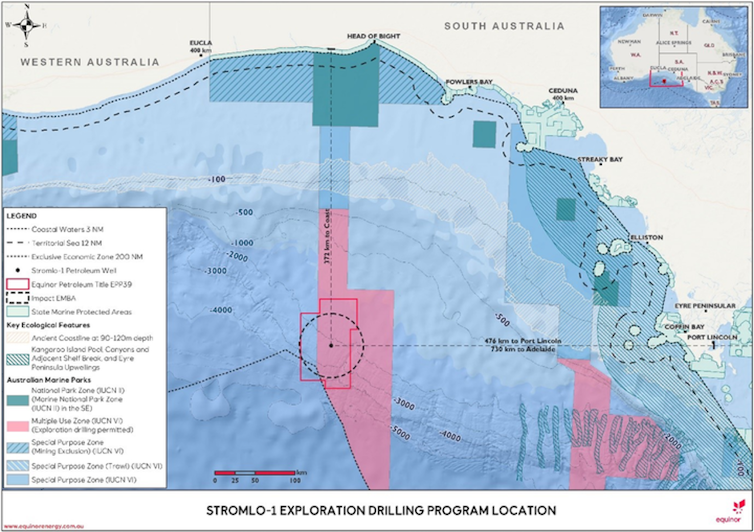

Exploratory drilling has taken place in the Bight since the 1960s. However, Equinor’s proposal involved drilling 370km off the coast in waters up to 2,500 metres deep. This brought extra technical complexity and made the proposal very expensive and environmentally risky.

Equinor’s environment plan also made overly optimistic assumptions and was inadequate in many ways, including the following:

– Environmental risk

Equinor said it was committed to ecologically sustainable development and would adhere to relevant environment regulations.

However, we believe the company did not comprehensively demonstrate how it would mitigate impacts on endangered species found within its well area.

Many species listed as threatened may have been affected by the drilling activities. These include a total of 28 listed migratory species, 20 listed marine species (including the endangered southern right whale, sea lions, dolphins, southern bluefin tuna and sharks) and five listed cetacean species.

Among the shortcomings in the environment plan, it did not outline how drilling would indirectly and directly affect the capacity of listed threatened species to restore their poulations, as is required under the Commonwealth Environment Act.

The Conversation contacted Equinor for a response to this criticism. Equinor said its environment plan “was accepted by the independent regulator in December 2019. The plan submitted and accepted demonstrated our ability to drill the exploration well safely”.

– Public consultation

Equinor conducted only limited public consultation – within a 40-kilometre radius of the well site. This excluded many relevant parties with a shared concern for the local environment.

The consultation approach also ignored the fact that if a significant accident occurred, such as the worst-case oil spill, there was a risk of harm to communities thousands of kilometres away.

It was particularly egregious that Equinor failed to consult any Indigenous organisations despite numerous Indigenous sea and land title claims that may have been affected by a spill.

Equinor also excluded 18 coastal councils from consultation, as well as conservation groups.

In response to this criticism, Equinor said it “engaged broadly with the community to provide information about our company and our plans for the Stromlo-1 exploration well, holding more than 400 meetings with stakeholders”. It said the consultation process complied with relevant legislation.

– Oil spill modelling

Equinor took a very conservative approach to oil spill modelling. Its modelling of the “worst case discharge scenario” predicted a far lower oil flow rate than modelling by BP in 2016 for the same well location.

But the scenarios Equinor developed would still have amounted to a catastrophic and unprecedented environmental event: a discharge of 42,387 barrels per day until the well was killed after 102 days, or 4,323,478 barrels of oil in total. This is a similar to the amount of oil estimated to have entered the Gulf of Mexico following the Deepwater Horizon disaster.

In response, Equinor said its oil spill maps “do not represent what a single spill would look like, or the area it would affect. To make sure we have planned for anything that could possibly happen, regardless of how unlikely it is, legislation requires us to form a single map by superimposing 100 different simulations of a worst-case oil spill under varying weather conditions”.

Why did Equinor jump ship?

Equinor says it abandoned its plans for commercial reasons – the same reason cited by BP and Chevron.

The company’s decision came just weeks after the federal regulator granted environmental approval to the company’s proposed Stromlo-1 well after three failed attempts.

So after pouring so much money and effort into the project, why would Equinor jump ship now? We believe other factors were also at play.

Read more:

Noise from offshore oil and gas surveys can affect whales up to 3km away

First, the project failed to gain a social licence. Public surveys showed 60% of people nationally and 68% of people in South Australia opposed Equinor’s plans.

Second, it faced ongoing legal hurdles. The Wilderness Society had mounted a Federal Court challenge to the environmental approval over Equinor’s failure to consult relevant parties.

Third, and more broadly, much of the world is moving away from fossil fuels. The European Investment Bank is phasing out fossil fuel financing and the International Energy Agency has called on oil and gas companies to lower their emissions, warning that not doing so “could threaten their long-term social acceptability and profitability”.

Europe is moving away from oil, in a move that threatens the offshore petroleum industry.

So what now?

Australia’s oil and gas industry is not going away. So in light of the risks, how do we protect marine life into the future? The answers may come from Equinor’s home country Norway.

The Norwegian government owns a two-thirds stake in Equinor. The government’s pension fund has announced plans to divest A$17 billion worth of fossil fuel stocks, and Equinor itself aims to reduce emissions from offshore fields and onshore plants in Norway by 40% by 2030, and to near zero by 2050.

Read more:

It’s time to speak up about noise pollution in the oceans

In Norway, oil wells are operated in accordance with a standard requiring companies to demonstrate “fitness to drill” before work begins. This is not required under Australian regulations, which apply the lesser standard of “good oilfield practice”.

In developing petroleum resources, The Norwegian Petroleum Act requires titleholders to take “a long-term perspective for the benefit of Norwegian society as a whole”. This requires contributions to the welfare, employment and improved environment of the nation.

Australia’s Equinor experience has made one thing very clear: in protecting both our environment and the interests of future generations of Australians from the effects of fossil fuel extraction, this nation still has a lot to learn.

Greg Bourne contributed to this article.![]()

Madeline Taylor, Academic Fellow, University of Sydney and Tina Soliman Hunter, Professor of Petroleum and Resources Law

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.