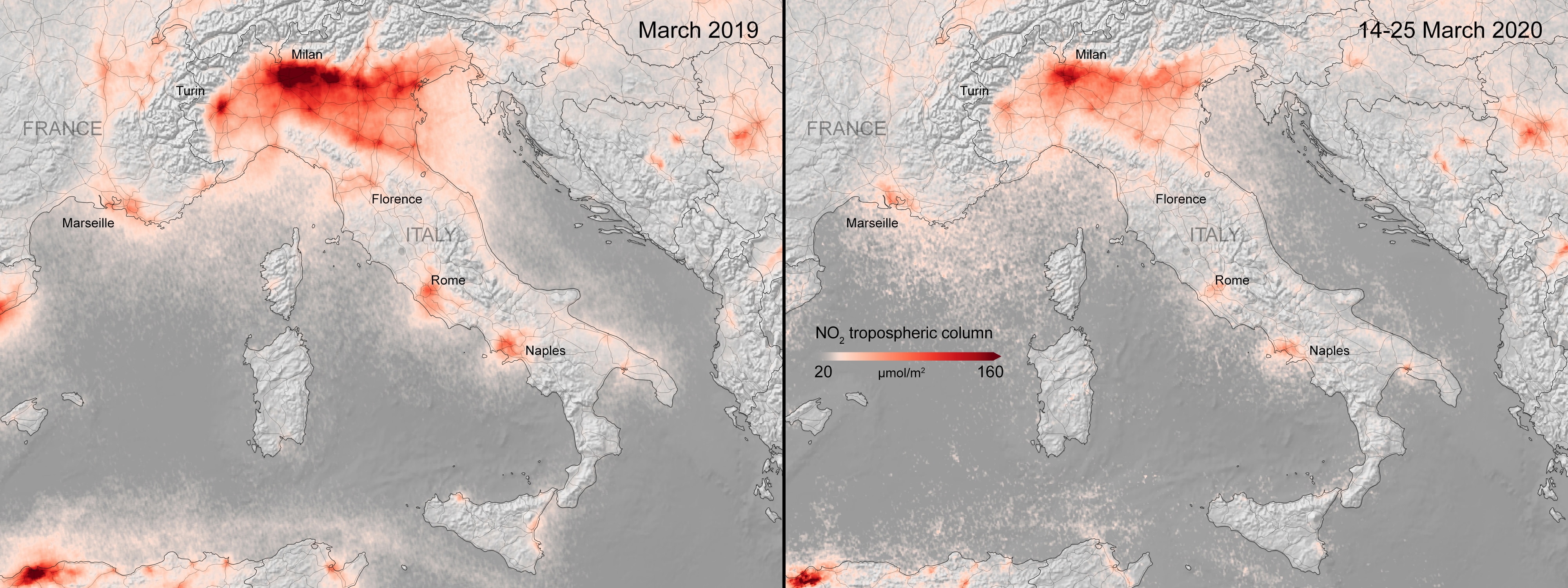

Imagine if we could live this way by de-carbonizing industry & transport instead of shutting them down?

Worldwide pollution levels drop amid Coronavirus measures

The shutdown of businesses and activities related to Covid-19 has also led to a decrease in nitrogen dioxide concentration across the world.

Data from the Copernicus Sentinel-5P satellite of the average nitrogen dioxide concentrations over Italy from March 2020 (R), compared to March 2019.AAP

The European Union’s space agency (ESA) has detected reductions in the pollutant nitrogen dioxide associated with shutdowns due to the coronavirus across the world.

New research is now looking at why the mortality rate was up to 12 percent in the northern part of Italy compared to approximately 4.5 percent in the rest of the country. Scientists at Aarhus University say they found a “probable correlation between air pollution and mortality in two of the worst affected regions in northern Italy.” Their research has been published in the scientific journal Environmental Pollution.

Prologue By Bergensia

Katie Gibbs, Swansea University; Andrew H Kemp, Swansea University, and Zoe Fisher, Swansea University

The world as we know it may never be the same. The global economy has slowed, people are living in isolation and the death toll from an invisible killer is rising exponentially. The coronavirus pandemic has imposed a harsh reality of bereavement, illness and unemployment. Many people are already facing financial hardship and uncertainty over future job prospects.

Early data suggest that the immediate psychological impact of the pandemic is substantial. There are also more uplifting analyses, however, suggesting the experience may help us change our lifestyles for the better. But are humans even capable of sustainable behaviour change?

We know that crises can lead to anger and fear. At a community level, these emotions can descend into acts of scapegoating, stigmatisation and discrimination. Environmental shocks and epidemics may also cause societies to become more “selfish”, electing authoritarian leaders and showing prejudice towards outsiders.

We also know that existing societal inequality – which is a threat to mental health – deepens after tragic events. Any psychological distress tends to be amplified in those who are less fortunate.

To change our behaviour for the better, we need to first overcome these challenges and boost well-being. Over the last three years, our group has given much thought to “well-being”. We define this as positive connections to ourselves, communities and our wider environment.

On a basic level, positive health behaviours are important to achieve individual well-being, such as eating healthily, sleeping well and exercising. A strong sense of meaning and purpose is especially crucial for overcoming major life events and realising “post-traumatic growth”. In the words of one of our colleagues – who has overcome multiple sclerosis – we must commit to “positivity, purpose and practice” during personal crises. This involves moving beyond ourselves and serving something greater.

Positive social ties and communities are therefore essential. Social relationships lay the foundation for personal identity and our sense of connectedness with others. This gives rise to positive emotions in an upward spiral relationship.

Recent research and scholarly work also demonstrate that we have an innate need to be connected with nature and other forms of life to feel good. Individuals who regularly spend time in nature tend to be happier and have a greater sense of meaning in life.

Nature makes us happy. Song_about_summer/Shutterstock

Unfortunately, it is no longer possible to discuss the link between the environment and happiness without considering the major threat that is anthropogenic climate change. This can give rise to the emotion of “solastalgia” – a state of grief, despair and melancholia resulting from negative environmental change.

The commonalities between the coronavirus pandemic and climate change are stark. Both challenges represent “environmental” problems that are socially driven. A major difference, however, is our global responsiveness to one, but not the other.

The abstract nature of climate change, along with the helplessness we feel in relation to it, contribute to our “sitting on our hands and doing nothing”. This phenomenon is known as “Giddens Paradox”. Perhaps the silver lining here is what coronavirus can and should teach us – that a commitment to action leads to change.

Change is possible

The Chinese word for “crisis” includes two characters, one for danger and another for opportunity. During the pandemic, many people have been forced to work from home – substantially reducing time spent travelling, as well as air pollution. This may continue, if we see the value in it.

Although not without its challenges, trials of flexible working patterns, such as the four-day working week, also demonstrate an array of benefits to individual well-being.

Coronavirus begs the question: why would we want to fully return to the workaholic status-quo when the end goal can be achieved in a different way, supporting well-being, productivity and environmental sustainability? Any small positive change helps us to feel further empowered. The pandemic has, after all, taught us that we can get by without shopping excessively and going on long-haul flights for holidays.

There is evidence that we can make behavioural changes following a crisis. We know that some preventive measures, such as respiratory and hand hygiene, can become habitual following a viral pandemic. Research has also shown that residents in New Jersey, US, became more likely to support environmental policies following two devastating hurricanes. Experiences of flooding in the UK have similarly been shown to lead to a willingness to save energy. Meanwhile, bushfires in Australia have boosted green activism.

Maintaining change

That said, research shows that positive change generally dwindles over time. Ultimately, we prioritise the restoration of societal functions rather than pro-environmental actions. Maintaining any change in behaviour is difficult and depends on many factors including motives, habits, resources, self-efficacy and social influences.

Positive psychological experiences, emotions and a newfound sense of purpose may hold the key to driving non-conscious motives towards environmentally sustainable behaviours. Emerging evidence also suggests that environmental education and nature-based activities can facilitate pro-sociality and community connectedness.

Fortunately, simple interventions such as walking and “mindful learning”, paying attention to the present, have been shown to promote openness towards ideas relating to the overlap between humans and nature. These things can help maintain behavioural changes.

Understanding that our psychological, social, economic, and natural worlds are part of an interconnected system also facilitates an ecological ethic towards protecting and preserving the natural world.

To achieve that, interventions grounded in fostering positivity, kindness and gratitude could be effective. We know that these things lead to sustainable positive transitions. Meditation focusing on love and kindness also enables positive emotions and a personal sense of community connectedness.

Keeping a journal outdoors could be motivating. Teechai/Shutterstock

Another intervention that can reduce stress and promote psychological well-being is keeping a journal. This could even boost pro-ecological behaviour when completed in nature.

The government’s responsibility

Some problems are simply impossible for the individual to fix alone, however – hence Giddens Paradox. Positive change by individuals will likely be temporary or insignificant, if not reinforced by policy or regulation. Organisations, industry and government have a big responsibility for promoting positive change.

A first step would be to enable the well-being of all citizens, by overcoming threats of inequality, xenophobia and misinformation in the aftermath of the pandemic. If we fail to do this, we will ultimately be neglecting opportunities for positive change and risking the very survival of our species. What we decide to do today and after the current crisis is of paramount importance.![]()

Katie Gibbs, PhD Candidate of Psychology, Swansea University; Andrew H Kemp, Professor and Personal Chair, Swansea University, and Zoe Fisher, Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Swansea University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.