AP Photo/Eric Risberg

Mary Alice Haddad, Wesleyan University

Being pro-environment was a winning strategy for this country’s mayors.

Twelve mayors in America’s 100 largest cities faced re-election battles during the 2018 midterms, and mayors – both Democrats and Republicans – who followed pro-environmental policies were rewarded. All six mayors who had demonstrated their commitment to the environment by signing the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy – including Stephen Adler of Austin, Texas, Greg Fischer of Louisville, Kentucky, and Libby Schaff of Oakland, California – won re-election. The other big city mayors in re-election battles weren’t so fortunate – two won, two lost and two are facing runoffs.

Of course, voters consider many issues when they cast their ballot. It’s unlikely that the environment was the deciding issue in these races. However, mayors that prioritize the environment seem to be making changes in their cities that please constituents. The positive election results in 2018 were not an anomaly – all 15 mayors who signed the covenant and sought re-election in the last two years have been victorious at the ballot box, usually by large margins.

Mayors with pro-environmental agendas aren’t just popular. I believe they are an important part of the answer to the global challenge of climate change.

As a scholar of civil society and environmental policy – this is just one of the positive signs I see not just in American cities, but around the world.

Climate change is urgent

A month before the election, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued its latest report about the risks associated with climate change. The news was bad. Our planet is now expected to reach a 1.5 degrees Celsius increase in average global temperatures as early as 2030. One billion people will regularly endure conditions of extreme heat. Sea levels will rise, exposing between 31 and 69 million people to flooding. Seventy to 90 percent of coral reefs will die. Fishery catches will decline by 1.5 million tons. And that is if we are lucky and keep the temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius, which will not be easy.

As my colleague Gary Yohe reflected in a recent New York Times article, “2 degrees is aspirational and 1.5 degrees is ridiculously aspirational.” At exactly a time when we need to become more ambitious in our efforts to tackle this global problem, the United States has pulled out of the Paris agreement and is dismantling many of its clean energy and other climate policies at home. One of my students recently expressed a common feeling of helplessness: “It makes me wonder if the best thing I can do is just go out in the backyard and compost myself.”

So, I’d like to say: There is hope. While the president of the United States may not be making much progress, many other people are. The election of pro-environment mayors and governors is one excellent sign.

Cities take the lead

A number of U.S. cities have gained global reputations for their innovative responses to the challenge of climate change.

Once one of America’s most polluted cities, Pittsburgh has demonstrated how creative collaborations with the private sector, nonprofits, philanthropists and academics can turn toxic urban environments into one of America’s most livable cities.

AP Photo/April Castro

Austin’s vulnerability to climate related disasters, including drought, wildfires and hurricanes, has made it especially aggressive about addressing climate change. It has committed to being net-zero greenhouse gas emitter by 2050. Its innovations in developing and spreading renewable energy have earned it awards in green technology, climate protection and redevelopment. Austin’s pro-environmental efforts are transforming the city into a more livable place for its residents and a better one for the planet.

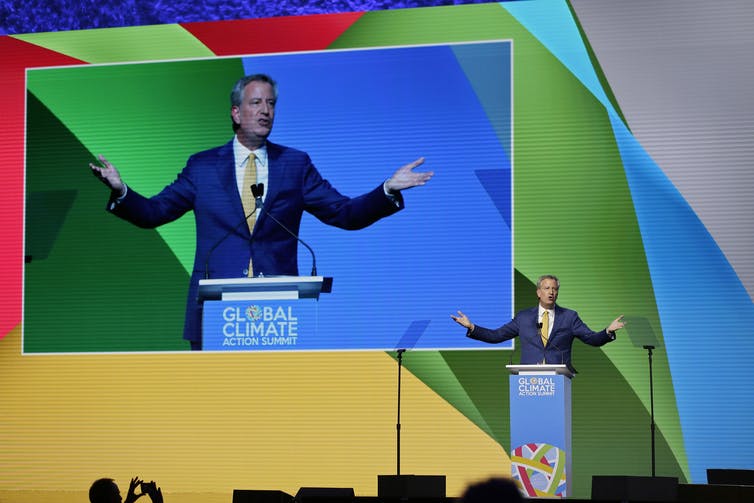

San Francisco, which reduced its carbon emissions by 30 percent between 1990 and 2016, cemented its global leadership position by hosting the 2018 Climate Action Summit this past September, which gathered 4,500 leaders from local governments, nongovernmental organizations and business together to address climate change. The summit resulted in numerous corporate and city commitments to become carbon neutral, as well as trillions of dollars of investment in climate action.

New York City reduced its emissions by 15 percent between 2005 and 2015. Its residents have a carbon footprint that it only one-third that of the average American. The mayor of the financial capital of the United States has also become a champion of oil divestment.

These American cities are not alone. They are part of a global movement working to combat climate change. The Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy has more than 9,000 local governments from 127 countries representing more than 770 million residents committed to making headway on climate change. C40, ICLEI, Metropolis, United Cities and Local Governments and other organizations are helping cities find solutions that work and implement them.

As in the U.S., global cities are also making significant progress on climate change. Tokyo reduced its energy consumption more than 20 percent between 2000 and 2015, with the industrial and transportation sectors making astounding 41 percent and 42 percent reduction respectively. By 2015, the city of London had reduced its emissions 25 percent since 1990, and 33 percent since peak emissions in 2000.

These cities are not waiting for presidents and prime ministers to act, they’re making changes right now that are improving the lives of the tens of millions of their own residents by improving air quality, reducing flooding risk and expanding green space, all while helping to bend the global emissions curve downward.![]()

Mary Alice Haddad, Professor, Wesleyan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.