Arnaud Exbalin, Université Paris Nanterre – Université Paris Lumières

The debate over the place of cars in cities may seem like a recent one, but in fact, was raging well before the first automobile even saw the light of day.

To better understand, let us take a look at the streets of Paris when the French Revolution was in full swing and when all the “cars” were still horse-drawn. Even then, speeding carriages in densely packed urban areas could be deadly, and they raised the same essential questions as cars do to today – in particular the relative importance of orderly behaviour, traffic management, freedom of access and the right of way.

An anti-car pamphlet

In 1790, an anonymous Parisian printed a pamphlet with a surprising modern title, “A Citizen’s Petition, or A Motion against Coaches and Cabs”. Passionately written, this 16-page text is simultaneously a moral treatise, a police memoir and a legislative motion, since it also contains propositions intended to be forwarded at the French National Assembly.

Little is known of its author except that he was probably a well-to-do citizen – perhaps a doctor – as he declares that he owns “a coach, a cab and four horses”. These, however, he is ready to “sacrifice on the altar of the country”, scandalised as he is by the brutality of drivers as they cross the city and disgusted by the “idleness and sloth of the rich”. Swayed by the ideas of the Enlightenment and praising the contributions of the Revolution, he asks: What is the worth of a free press, religious tolerance and the abolition of state prisons if “one cannot go on foot without being exposed to perpetual danger?” Indeed, at a time when universal human rights were being proclaimed, Parisians continued to be killed by cars, to the complete indifference of legislators. The pamphlet’s author therefore proposed to “fulfil” the work of the Revolution by prohibiting the use of coaches in Paris.

In 1790, a year after the “Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen”, the political situation in Paris was in many ways unprecedented. On the roads, however, the domination exercised by coach drivers over pedestrians remained unchanged.

Congestion in Paris

The wildly rushing vehicle is a literary topos that can be traced back to the congested streets of Paris of the 17th and 18th centuries. Featured in works by Paul Scarron and the Abbé Prévost, it can also be found in Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux’s famous satire on a collision between a cart and a coach. In his poem, a nightmarish “embarrassment” is depicted:

A coach’s wheel strikes a cart at a corner,

And, by accident, sends both into stale water.

Too soon, a mad cab, trying desperately to rush past,

In the same embarrassment embarrasses not the last,

For promptly, twenty more coaches soon come into the long line

Leading the first two, to quickly become over fourscore and nine.

If such “embarrassments” or “strife” (as traffic jams used to be called) inspired the writers of fiction, it was also because they were a daily reality of the streets of the Ancien Regime.

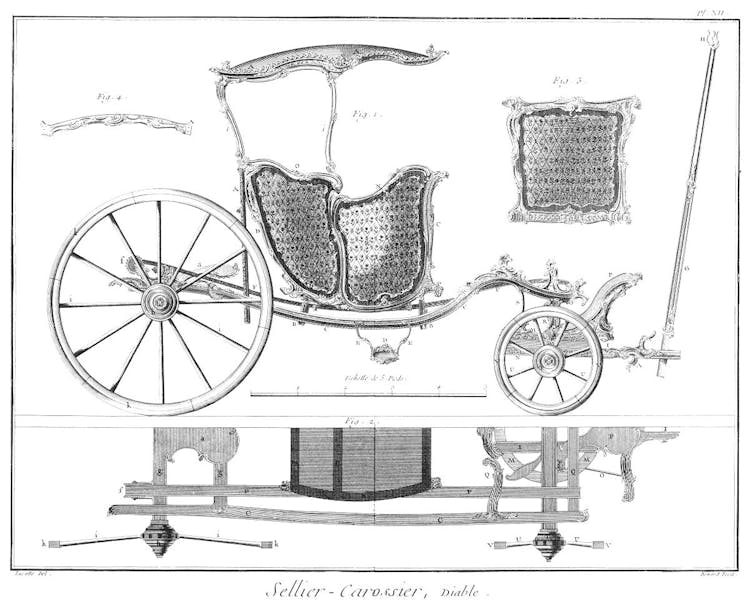

Library of the Decorative Arts/BNF

There are hardly any urban chronicles, police memoirs or travel stories that do not mention showers of mud, clouds of dust, the din of iron-rimmed wheels disturbing the peace of the sick, roads blocked by a coach or a cart manoeuvring a tight corner.

The killer car

What appears radically new in the writings of the late 18th century, however, is the theme of the killer car. This can be found in the work of Louis Sebastien Mercier and Nicolas Restif de la Bretonne, and also in another anonymous pamphlet, this from 1789, titled “The Assassins, or A Denunciation of the Tyrannically Abusive Nature of Cars”. In this pamphlet, the author virulently attacks the English-style phaetons, whiskies, devils and other cabs as these lighter vehicles were particularly adapted to city traffic and were therefore “as fast as eagles”.

His argument goes that highwaymen, ready to kill a traveller for his money, are the assassins of the road. But in Paris, the assassin is “the one who, without passion and without need, suddenly flings open the doors of his household, rushes like a madman toward a thousand of his fellow men and presses them, with all his might, with a fast cab and two steeds.” It is therefore the social battle between pedestrians and car users that his texts exemplifies.

Pedestrians and coach-riders in Paris

In a palpable way, this second text confronts two opposing developments that ran throughout all of the 18th century.

One was the prodigious increase in the quantity of horse-drawn traffic within Paris, linked to the population’s ever-increasing need for food and merchandise. With its 700,000 inhabitants, it already had very hungry belly… As Daniel Roche indicates, however, the increase in traffic can also be explained by the rise in passenger circulation. During the 17th century, the carriages in circulation were nearly exclusively the coaches used by royalty and nobility. Later, the emerging middle classes of merchants, officers, bankers but also master-artisans and priests, who all previously travelled on foot, by mule, and at best on horseback, began to use the lighter and faster cabs.

Château de Versailles

Owning a car, in 1789, in Paris, remained the privilege of the nobles and the richer burghers. It meant keeping a coachman or lackey, owning a stable for the horses and a shed to store hay, straw, water and oats. The development of hired coaches and cabs, the ancestors of today’s taxis, that could be rented by the day or by the hour, gradually broadened the usage of passenger cars.

According to plausible estimates, in Paris the number of cars surged during the 18th and 19th centuries, rising from only 300 at the beginning of the 18th century to more than 20,000 by the French Revolution – an increase of 7,000 percent. Long before the mass production of the automobile, the car had therefore already become a commonplace feature of Paris’ streets.

An opposing development within enlightened circles was to travel by foot, like the humbler Parisians. The idea was not so much to go from one place to another, but to promenade. Therefore, the elites gradually stepped out of their coaches, carriages and cabs to walk along the tree-lined boulevards and through the parks and gardens. For the philosophers of the Enlightenment, including Jean-Jacques Rousseau, walking was a virtue that stood in contrast to the sloth of those who travelled by coach. During the Revolution, the pedestrian even became a major political figure and was embodied in the sans-culotte.

Cars: a primary source of insecurity for Parisians

Let us now imagine a scene often depicted by the Parisians of the day. You are quietly walking along the haut du pavé (the higher part of the street) of a narrow and crowded road. On one side is a vendor’s stall, on the other, leftover rubble due to roadworks, a little further on is an open-air forge encroaching on the road, above is the shop-sign of a cabaret forcing passing coachmen to dangerously swerve their vehicles. Suddenly, powered by two spirited horses, a cabriolet, weighing nearly 700 kg and devoid of any effective braking system, engages into the street at full speed. The driver, pressed by the owner of the vehicle, cracks his whip while shouting “Aside! Aside!”. What then? How to escape the wheels of the car when there is neither curb nor sidewalk?

In his Scenes of Paris, Jean-Sebastien Mercier narrates how, on three occasions, he was the victim of such homicidal cars. The anonymous citizen in the “Motion against Coaches and Cabs” provides chilling statistics: every year, more than 300 people were either killed instantly or suffered fatal injuries because of cars. The author does not, however, count all the pedestrians who were crippled or lost a hand, arm or leg. Nor does he speak of the thousands of pedestrians permanently scarred by the whips from angry coachmen.

Greater speed, more crashes

Yet were the crashes more numerous at the end of the century than at its start when the Parisians, now all Citizens, felt freer to take to their pens and denounce the excesses of the drivers of horse-drawn cars? What is certain is that the speed of the vehicles increased dramatically during the Age of Enlightenment. This was first for technical reasons: the newly introduced cabs were lighter and more manoeuvrable than the heavy coaches and could reach speeds of up to 30 km/h on major roads. Second, the multiplication of driveways, the alignment of the facades and the creation of large boulevards and thoroughfares enabled new heights of speed hitherto impossible to reach in town, even when the driver ignored the limitations fixed by the police.

Thus, not only did cars mark the bodies of Parisians, they also durably transformed the face of the city itself. This process continued and accelerated, with pedestrians even being excluded entirely from excluded entirely from certain roads. In recent years the city has pushed back, and even banned cars where pedestrians were once banned, on the right bank of the Seine.

The price of a life

In the 18th century, the victims of car accidents in the capital were mostly the children playing in the street, the elderly or impaired, porters bearing heavy loads and, generally speaking, any inattentive or distracted pedestrian.

When an crash took place, witnesses and police commissioners had to determine responsibility. If the victim was crushed the carriage’s rear wheels, it was simply hard luck. If they were been caught by the small front wheels, however, compensation could be claimed – usually a small sum of money was given on the spot to settle the affair. What then was the price of a pauper’s crushed leg? Most of the time, neither the coachman nor the owner bothered to stop but simply continued on. It was this profound inhumanity that angered the authors of the pamphlets.

Today, fewer people are killed by cars in Paris annually than at the end of the 18th century – about 30 deaths in 2017. There are still many more injuries, including an increasing number of cyclists. In Paris, this is mostly seen as a problem of public health and security as air pollution – a significant portion of which are emitted by vehicles – cause up to 7 million deaths per year, according to World Health Organisation. But even if cars emitted no pollutants, they’d remain deadly for pedestrians.

Banning cars from the capital

It is in the form of a potential decree, comprising 10 articles, that the first anonymous citizen formulates his proposal against coaches and cabs. For him, cars should be tolerated within city limits only if undertaken by a single rider on horseback, by a coach entering or exiting the city, or for those with medical emergencies. It is also proposed that coaches and cabs should be replaced by a sufficient number of sedans stationed at key junctions, with their fares clearly displayed.

Château de Versailles

The author of the pamphlet is fully aware of the implications of his pamphlet, “You will object that I will ruin a large number of Citizens.” Limiting the individual usage of horse-drawn cars would necessarily affect a whole section of the urban economy: the “wheelwrights, painters, leather-workers, saddlers, coachbuilders and farriers” but also “those renting out carriages, the coachmen […] and servants ”. He argues that by multiplying the number of sedan chairs, many new jobs would be created. More porters and craftsmen capable of manufacturing sedans would be needed. Savings would also be made by those having to pay for the food, care and stabling of horses. The stables themselves, occupying much of the habitable ground floor space of the capital, could be replaced by housing for “all our inhabitants living in mediocrity”. As to the courtyards, the pamphleteer suggests that their cobbles be removed and be replaced by lawn, vegetable gardens and orchards. Already, the car-free city pointed to another utopia, that of a leafier, greener city.

The invention of the sidewalk

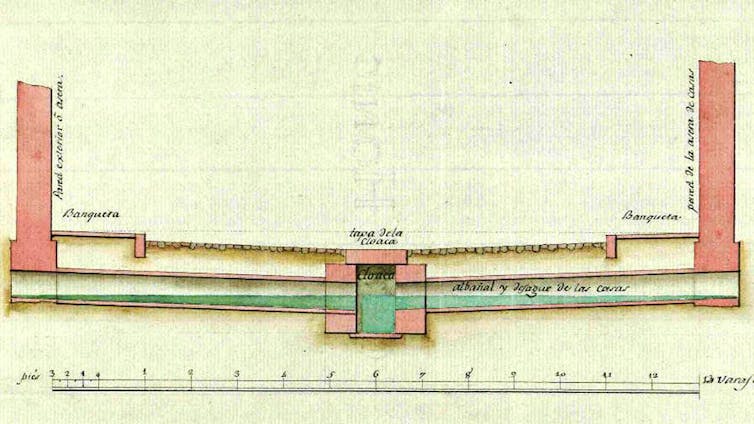

The anonymous citizen – who was also an anglophile – further proposed to generalise the construction of sidewalks, as these existed in London. He called for each new street to include a “sidewalk not be less than four feet wide”, about 130cm. Because the proposal was perceived as difficult to implement economically and politically, and potentially socially explosive, it was never discussed in the National Assembly.

This idea fared better in history, however, and suggests that the choice to develop cities by separating the flows of cars and pedestrians, and by reserving for the latter a portion of the street, was favoured very early by urban governance policies.

Under the Romans, for example, sidewalks existed, but gradually disappeared during the Middle Ages, as their layout was considered too restrictive for medieval cities. London and the larger English cities were the first in Europe to replace the medieval road stones and ramparts with sidewalks during the end the 17th century. In Mexico City, about 10 km of sidewalk were built in the 1790s.

At the time that the “Motion against Coaches and Cabs” came into print, sidewalks were almost totally absent from Paris, and existed only along the Pont Neuf, the Pont Royal and the Odeon. During the 19th century, they became more numerous, especially in the city centre. The suburbs were serious under-equipped until the early 20th century,

Since their generalisation, sidewalks have saved the lives of millions of city dwellers throughout the world. However, the full history of the relationship between pedestrians and cars in the city remains to be written.

The text was translated from the original French by Stephan Kraitsowits.![]()

Arnaud Exbalin, Maître de conférence, histoire, Labex Tepsis – Mondes Américains (EHESS), Université Paris Nanterre – Université Paris Lumières

Cet article est republié à partir de The Conversation sous licence Creative Commons. Lire l’article original.