Sergsta/Shutterstock.com

Margot Susca, American University School of Communication

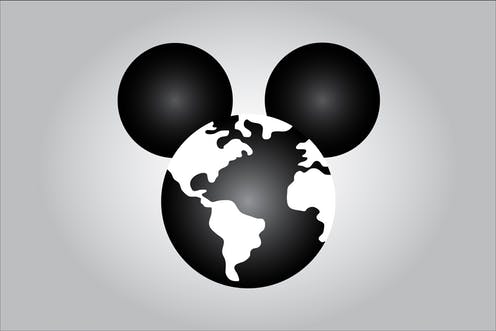

In the U.S., only a handful of media companies control what children and adults watch and read.

Now that number could get even smaller.

The proposed US$52.4 billion merger of Disney and 21st Century Fox would merge the first and third largest film companies in the world. Marvel Studios, Lucasfilm, Pixar, Searchlight, 20th Century Fox and Big Sky would all be under the same umbrella. Disney would also acquire control of TV channels like FX and National Geographic, adding to a portfolio that already includes ABC and ESPN. It would have majority stake in Hulu, which would position the streaming service to take on Netflix head-to-head in what many industry insiders expect will be a battle for market control.

As someone who studies global media power, I find the potential Disney-Fox merger troubling not just because one corporation will control production of narratives about popular culture and politics on television, film and streaming services, but because it will also create a media powerhouse worth so much that it could be as powerful as a state actor on the world stage.

‘Weapons of mass distraction’

For children and adults, media isn’t just entertainment. It is, in many ways, the tapestry of American life.

We grow up in front of the television screen, the silver screen and the computer screen, spending in the United States an astounding 12 hours daily engaged with media. It shapes our attitudes and beliefs, our likes and dislikes, our wants and desires and even our basic definitions of what it means to be normal.

Studies have found that Americans’ attitudes about everything from terrorism to race relations are largely formed by what they watch and hear. For example, a 2015 study was able to show that negative stereotyping of Muslims in news reports led to increased support for military action against Muslim countries.

Meanwhile, fictional television shows like “Homeland,” “The Americans” and “24” routinely cast foreigners as villains, making it easier for audiences to demonize citizens from other countries and immigrants. These attitudes have been shown to have a real effect on public policy.

Advertising to children is a $17 billion industry. According to the Campaign for a Commercial Free Childhood, children’s ads have all been connected to “eating disorders, precocious sexuality, youth violence and family stress,” while contributing to “children’s diminished capability to play creatively.”

As is the case with all businesses, the bottom line for media companies trumps any consideration of the public good. Studios ultimately produce shows that attract the most viewers and sell the most ads and movie tickets: cheaply produced reality television, celebrity gossip, political drama, and films packed with action and special effects.

The result is a media system that has become what media scholar Marty Kaplan calls a “weapon of mass distraction.”

A consolidation frenzy

Media control, then, has powerful implications in our society: The stories that appear influence how citizens make sense of the world.

When journalist and media critic Ben Bagdikian wrote his 1983 book “The Media Monopoly,” 50 companies controlled a majority of what Americans watched, read and heard.

Bagdikian predicted that further media consolidation of ownership would weaken coverage of lobbying, environmental issues, war, labor fights and corporate wrongdoing.

By the time he wrote his sequel in 2004, Bagdikian’s predictions had largely come true. But even he didn’t think that 90 percent of American media outlets would fall under the control of just five big media corporations. He wrote that these conglomerates operated as a kind of cartel that controlled our “most important institutions,” from newspapers to film.

Danny PiG, CC BY-SA

Disney, of course, was one of the five media conglomerates Bagdikian named. Another was Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp., which, at the time, included 21st Century Fox.

Money talks

If the $52 billion price tag sounds big, consider this: The payoff will be massive. The hybrid corporation control will give Disney a third of all domestic box office revenue, which, in 2017, amounted to about $3 billion.

Because the deal further shrinks the dwindling number of voices controlling media, Disney’s merger with Fox has a long way to go to pass Department of Justice muster. Three major anti-trust laws are supposed to guide Department of Justice principles related to mergers and the resulting market conditions left in their wake.

But I expect we’ll see what’s happened in the past when regulators have attempted to control the ownership structure of other media conglomerates: a massive lobbying campaign. The $72 billion deal that merged Comcast and AT&T Broadband in 2001 was given the go-ahead. A decade later, Comcast bought NBC Universal for $30 billion, a merger that passed both FCC and Department of Justice scrutiny after being called a “lobbying frenzy” by Roll Call.

Disney already spends millions of dollars annually lobbying Congress, the U.S. State Department, the Federal Communications Commission and the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, the federal agency responsible for negotiating with China to alter how it accepts and runs Hollywood films.

I also predict this merger will strengthen Disney’s bargaining power with China, which controls film’s release dates. China, the world’s second-largest film market, typically blacks out American films during crucial summer blockbuster months to focus on domestic films, and it allows just 34 foreign films to be released each year. Yet some believe China will be more willing to negotiate with the mega-company that will emerge after the merger because of its sheer financial clout.

The merger, of course, will also influence what information reaches Americans, including content citizens need to govern themselves in a democracy.

Disney shares members of its board of directors with companies like Anheuser-Busch, Chase Manhattan, Coca-Cola, Unilever and Pfizer. Citizens should ask: How might this influence the information disseminated about food, banking regulations, consumer products and pharmaceuticals?

And consider how a stronger China-U.S. media alliance could impact U.S. films, television and news. Would American media companies be hesitant to cover human rights violations, factory conditions or pollution in Asia for fear that they would anger the Chinese government and, therefore, lose bargaining power and access to audiences?

What gets left out of coverage is sometimes as important as what makes it in.

![]() If just four companies get to decide, we should all be concerned.

If just four companies get to decide, we should all be concerned.

Margot Susca, Professorial Lecturer, American University School of Communication

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.