Greg Goebel/Flickr, CC BY-SA

Bradley Handler, Colorado School of Mines; Matt Henry, University of Wyoming, and Morgan Bazilian, Colorado School of Mines

These are very challenging times for U.S. fossil fuel-producing states, such as Wyoming, Alaska and North Dakota. The COVID-19 economic downturn has reduced energy demand, with uncertain prospects for the extent of its recovery. Meanwhile, rising concern about climate change and the declining cost of renewable energy are precipitating a sharp decline in demand for coal in particular.

As a result, fossil fuel-dependent states and communities face the prospect of budget shortfalls and lower employment for the next several years. As researchers who study energy from economic, cultural and public policy perspectives, we believe that it is time for these states to develop long-term plans to diversify their economies and help ensure just and equitable transitions.

The idea of a just transition emerged from North American labor law, and has become part of international discussions about making societies more environmentally sustainable. It centers on protecting workers’ rights and livelihoods as they move out of declining industries.

In our view, just transition programs likely are the best way for these states to build more sustainable and diverse economic bases, reducing their reliance on fossil fuel production as a revenue source. To support secure, family-sustaining jobs as global fossil reliance declines, they will need to create new, lower-carbon economies.

From boom to bust

Fossil fuels enrich producing states through multiple revenue streams. They include taxes and royalties tied to the value of production; sales taxes on hydrocarbons; use taxes on equipment; and income taxes on industry employees’ wages.

Texas earns the most of any state from energy production, generating US$16.3 billion in fiscal year 2019, which was 7% of the state’s revenue. The states that are most reliant on energy are Alaska, where it accounted for 70% of state revenues ($1.1 billion) in fiscal 2019; Wyoming, where energy and other minerals yielded 52% of state revenues ($2.2 billion) in FY2017; and North Dakota, which reaped 45% of its revenues ($1.6 billion) from energy production in fiscal 2017.

Production declines and workforce reductions can have major economic impacts in fossil fuel states. For example, Wyoming is forecasting that it will have 29% less money in its General Fund than it previously expected in fiscal years 2021-22. Alaska is projecting an estimated 18% budget deficit in fiscal 2021.

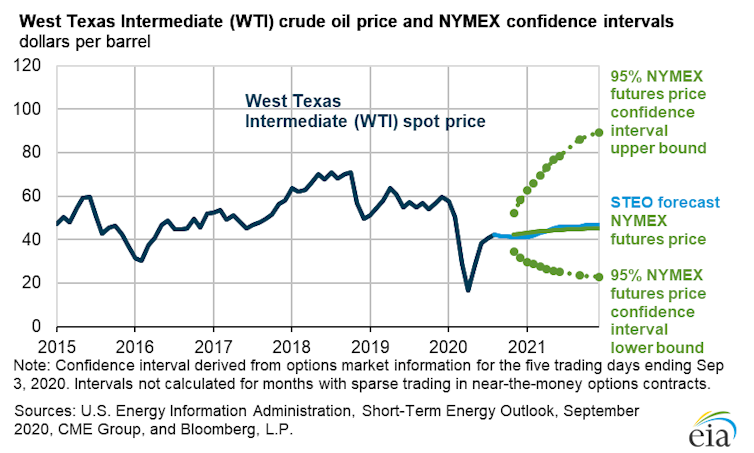

Even assuming that oil and gas production recovers from FY2020-2021 lows, these states expect to be forced to close the funding gap for the next several years.

EIA

Cultural and political roadblocks

Wyoming illustrates the challenges that a changing energy landscape posse for energy states. In the near term, the state is forecasting a 54% decline in taxes related to fossil fuels owed it in fiscal 2021-22 compared to the previous year. According to data that we obtained from the U.S. Department of Energy, estimated coal production in April-June of 2020 was down nearly 45% from the prior five-year average, reflecting national trends.

More structurally, experts and coal producers have acknowledged that thermal coal – the type used to make electricity – is in permanent decline. State officials have sounded the alarm about an industry “under siege,” while seeking ways to keep coal production afloat.

These efforts include preventing utilities from shutting down coal-fired power plants ahead of schedule, investing in making coal-fired energy cleaner and finding low-carbon uses for coal as a source of products, which can range from building materials to carbon composites and computer memory devices.

Meanwhile, studies show that Wyoming residents receive from the state up to 10 times the value in services that they pay in taxes, thanks largely to fossil fuel-related taxes. These trends clearly can’t continue in parallel: As coal revenues fall, state spending will have to contract.

But as the state considers its future, cultural and political factors influence public views as much as economics. Wyoming’s longstanding ethos of rugged individualism makes residents reluctant to accept outside economic assistance. Its coal industry workers have long taken pride in their role in providing a source of electricity throughout the United States.

When the utility PacifiCorp recently announced plans to close 20 of its 24 coal-fired power plants in the West, including several in Wyoming, and invest in lower-cost wind, solar and energy storage, some workers and legislators argued that the company was trying to please customers in left-leaning states. Ongoing wind energy investments are poised to partially offset fossil fuel job and revenue losses. But some Wyoming residents argue that wind projects

could harm conservation, outdoor recreation and tourism, the state’s second-largest industry.

What just transitions require to succeed

Just transition programs typically focus on promoting economic development, attracting investment to stimulate entrepreneurship and retraining workers. They often provide income support to bridge the period between jobs.

State and local leaders may seek to promote specific industries that reflect larger policy goals – for example, wooing solar companies to promote decarbonization. A number of current economic development policy proposals take this approach, including Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden’s Build Back Better plan. However, we believe new businesses are best developed at the community level so that they incorporate local intellectual capital, worker skills and natural resources, and get more political buy-in from the communities.

There are several examples of successful just transition programs. One is Project QUEST in San Antonio, which highlights the benefits of “local contextualization” and has helped workers transition from manufacturing to health care, information technology and other trades.

The province of Alberta, Canada, achieved considerable buy-in from labor unions and electricity companies as it accelerated its retirement of coal power, in part by leveraging its natural gas resources and working with local labor unions. And the New Economy program, promoted by the nonprofit organization Appalachian Voices, is amplifying residents’ ideas for new economic initiatives to offset job losses and shrinking coal tax revenues. This kind of participatory approach to economic diversification is critical for securing community support and generating novel ideas for economic development.

These programs are likely to require significant financial investment. Wyoming, North Dakota and Oklahoma don’t have a lot of debt, so they could borrow large sums to pay for these programs.

Alaska, Texas, New Mexico, Wyoming and North Dakota also have substantial sovereign wealth funds – state-owned accounts, funded with revenues from natural resource extraction. These funds could help fill the gap, but only if politicians can withstand pressure to use the money in more popular ways, such as Alaska’s annual payouts to state residents from oil revenues.

A chance for more sustainable communities

Fossil fuel states’ windfalls from energy development and their free-market cultures can make it hard for residents to accept their dependence on industry taxation and vulnerability to industry downturns. Solutions that involve increased taxing and spending are likely to face stiff political headwinds, even if sovereign wealth funds offer help.

The choices that states make as they navigate a rapidly changing energy landscape will have major implications for their workers and communities. Just transitions will require significant, focused investment, committed institutions and deep community engagement. While these processes aren’t likely to be easy, they offer the chance to build sustainable and environmentally friendly economies that can help these states thrive in the future.![]()

Bradley Handler, Non-resident Fellow, Payne Institute of Public Policy, Colorado School of Mines; Matt Henry, Scholar in Residence, University of Wyoming, and Morgan Bazilian, Professor of Public Policy and Director, Payne Institute, Colorado School of Mines

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.