Peter Hopkins, Newcastle University; Gurchathen Sanghera, University of St Andrews, and Kate Botterill, Edinburgh Napier University

Immigration and national identity currently are at the forefront of the public conscience. In France, the burkini ban and in the UK proposals for migration controls following the Brexit vote are dividing communities. The growing tensions mean that many ethnic and religious minority communities are increasingly experiencing racism in their everyday lives.

In 2015, Islamophobia reportedly increased by 200% in the UK while anti-Muslim attacks in the US grew by 78%. The term Islamophobia is defined as “unfounded hostility towards Islam”. This includes “unfair discrimination against Muslim individuals and communities” and the exclusion of Muslims from political and social affairs.

But the term “Islamophobia” is somewhat confusing: it supports the idea that there is only one “Islam” and implies a “fear” of it. Some have argued for new, more accurate terms such as anti-Muslimism. Like the word itself, the phenomenon of Islamophobia is equally complex, and cannot be put neatly into a box. Here are some of the ways it affects everyday life.

1) It isn’t only experienced by Muslims

It is not only Muslims who are targeted by Islamophobic racism. A diverse range of people from different ethnic and religious minorities also encounter it on a daily basis, mostly as a result of people assuming that they are Muslims. Sikhs, Hindus, other south Asians, those with African heritages and even some central and eastern European migrants are all lumped into one category. This can make other religious and ethnic minorities insecure in public spaces, and in their everyday encounters with others.

Cloud Mine Halloween/www.shutterstock.com

2) It is shaped by geopolitics

Experiences of Islamophobia are strongly interconnected with geopolitical events such as 9/11, the 2005 London bombings, the 2013 Woolwich incident and the ongoing conflict in Syria. Research shows that experiences of racism and Islamophobia increase shortly after such events before declining gradually.

In addition, our own research has found that the reporting of such events in the mainstream media contributes to the negative stereotyping of Muslims. We interviewed young people, aged 12 to 26, who claimed that references to Muslims as “extremists” and as a “threat” to British ways of life in the media skew the public’s perception of Muslim communities – despite frequent campaigns to challenge such negative associations.

3) It ignores the diversity of Muslim communities

Islamophobia makes it appear as if “the” Muslim community lacks any internal diversity. Muslims can be of any ethnicity and have varying attitudes with regards to how and when they practise their religion. Muslims also have different attitudes to, and ideas about, issues such as feminism, gender and sexuality. To lump them all into one category is to overlook the diversity of Muslim communities.

4) It’s different for men and women

Women and men do not experience Islamophobia in the same way. Women are more likely to experience anti-Muslim sentiment, particularly if they are wearing a headscarf, hijab or burka. In fact, 61% of Islamophobic incidents reported to Tell MAMA in 2015 were against women, and 75% of these victims were visibly Muslim. For Muslim men, markers of Muslimness – such as having a beard, brown skin or wearing “Asian clothes” – increase the likelihood of them experiencing Islamophobia. Although men were less likely to experience Islamophobia than women, when they did, it was similar in nature, including verbal abuse, physical assault and threatening behaviour.

5) It can make Muslims wary of public places

Despite heavy coverage of Islamophobic attacks on public transport, our research has found that this racism is not restricted to specific places. It occurs in schools, colleges, neighbourhoods, public spaces and at airports.

Significantly, it also shapes Muslims’ mental maps of public spaces, and where they feel it is safe or unsafe for them to visit. Muslims are inclined to moderate their movements in public spaces and this at times feeds into debates about self-segregation and the accusation that Muslims are living parallel lives.

6) Attacks vary in intensity and nature

Physically aggressive forms of Islamophobia include outright extreme violence, as well as things like headscarfs being pulled off by fellow passengers on public transport. There is also name-calling, taunting, or individuals being made the subject of jokes and “banter” in public. Online Islamophobia is prevalent on social media sites, too, although such contexts also provide a space to challenge such behaviour.

The responses to these different forms of Islamophobia by those who experience it are also variable. Our research found that young people demonstrate resilience to so-called banter and name-calling. But for others, Islamophobia may mean subtle forms of avoidance and exclusion, such as being stared at, not having someone sit next to you on the bus or experiencing a general sense of social distance.

7) Islamophobia is reproduced institutionally

Government institutions can reinforce and reproduce Islamophobia through counter-terrorism initiatives, such as the UK’s Prevent strategy for schools. There are a number of concerns about the ways that educational institutions monitor and survey students who look Muslim as a result of these policies, and how this leads to Muslim students feeling increasingly monitored when on campus.

Anti-Islamic sentiment is also experienced in the workplace – 100% of participants in a small focus group recently said that they had directly experienced, witnessed, or have family members who had experienced discrimination in the workplace. Some Muslims may be reluctant to challenge such forms of discrimination as a result of what they see as aggressive secularism and feel silenced as a result.

8) Young people build new strategies

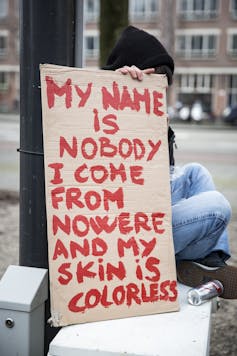

Young people have had to develop a range of strategies in order to negotiate and resist Islamophobia. Some have talked about adopting “self-securitising” techniques to mitigate against the harm of feeling “targeted”, avoiding certain spaces or conversations. Others, like Australian researcher Rhonda Itaoui have been more resistant and challenged Islamophobia through proactively speaking out against it – but not all have the confidence to do this.![]()

Peter Hopkins, Professor of Social Geography, Newcastle University; Gurchathen Sanghera, Lecturer, University of St Andrews, and Kate Botterill, Lecturer in Human Geography, Edinburgh Napier University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.