Atlanta Journal-Constitution/Youtube

Rashawn Ray, University of Maryland

Unsteady cellphone footage follows a jogger – an apparently young, black man – as he approaches and attempts to run around a white pickup truck parked in the middle of a suburban road. Moments later he lies dead on the ground.

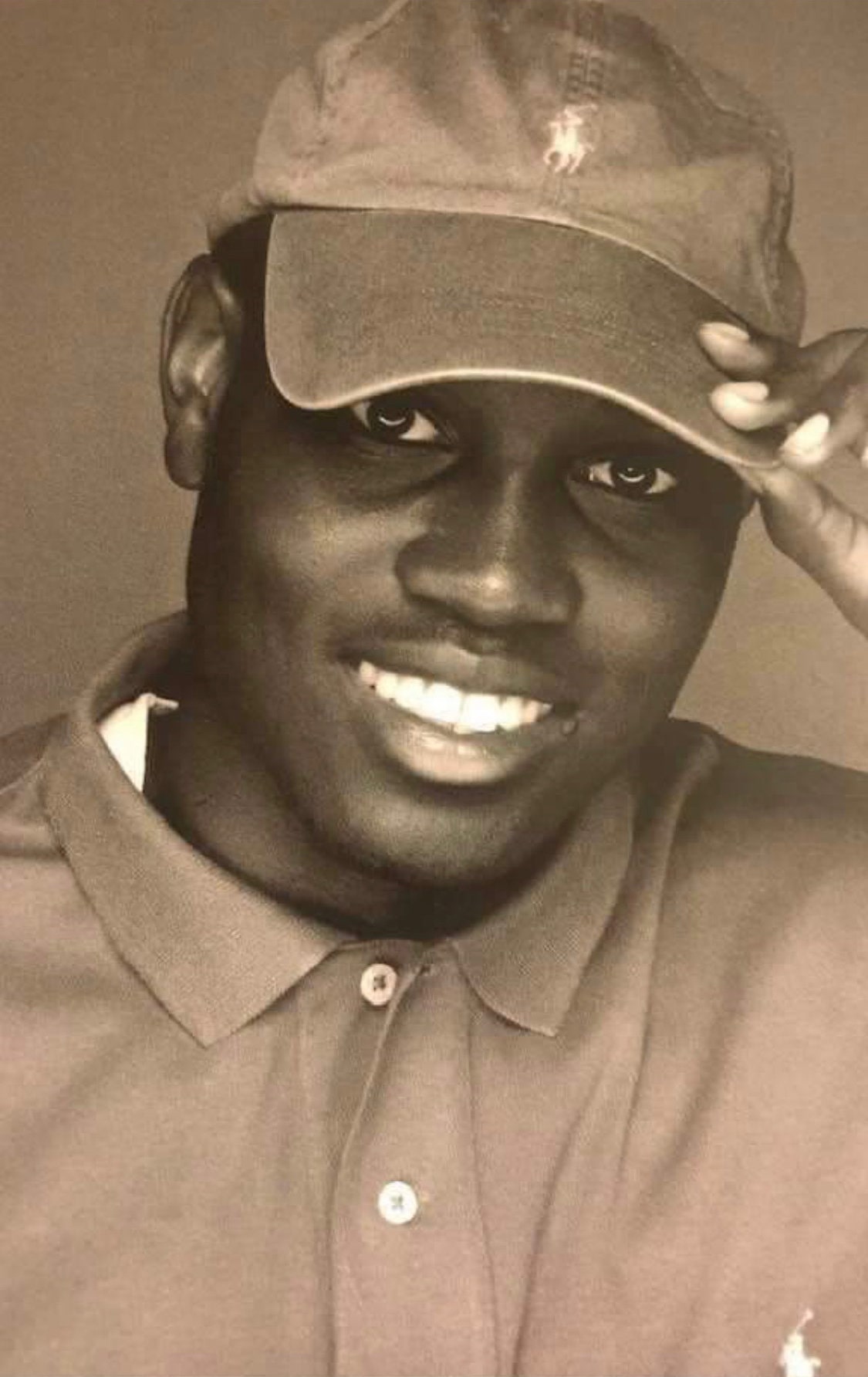

The killing of Ahmaud Arbery took place on Feb. 23, after the 25-year-old was confronted by Gregory McMichael, a 64-year-old former police officer and investigator for the Brunswick, Georgia district attorney’s office, and his 34-year-old son, Travis. It took 10 weeks to gain widespread attention with the circulation of video footage on social media, prompting revulsion and calls for justice.

Gregory and Travis McMichael were both taken into custody on May 7 on charges of murder and aggravated assault.

Warning: This video includes graphic images.

Death in suburbia

But the killing of Arbery by people with links to law enforcement raises important questions over why it took so long to make arrests in the case and the so-called blue wall of silence that extends from law enforcement agencies to prosecutor’s offices and courtrooms.

But there is a separate question that needs to be asked: Why do these incidents seem to occur in certain types of neighborhoods? Satilla Shores, where Arbery was killed by the McMichaels, is predominately white and suburban. It evokes memories of the killings of Trayvon Martin, Jonathan Ferrell, Renisha McBride and Tamir Rice.

As a sociologist and public health scholar, I have studied physical activity and how it varies by race and social class. I know that the exact behaviors that are encouraged to extend life for all are the exact ones that can end the life of men like Ahmaud – in short, jogging while black can be deadly.

In 2017, I published a study on physical activity – focusing on where and how people exercise, and breaking this down by race and gender. I surveyed nearly 500 middle-class black and white professionals around the United States. The research also included in-depth interviews, focus groups and observations of public spaces in cities with varying racial and class compositions including Oakland and Rancho Cucamonga, California; Brentwood, Tennessee; Bowie, Maryland; and Forest Park, Ohio.

I found that race and place significantly inform where people engage in physical activity: White men, white women and black women living in predominately white areas were significantly more likely to engage in physical activity in their neighborhoods. Black men living in predominately white neighborhoods, however, were far less likely to engage in physical activity in the areas surrounding their own homes.

Good neighbors?

Black men I interviewed who had jogged in white neighborhoods where they lived reported incidents of the police being called on them, neighbors scurrying to the other side of the street as they approached, receiving disgruntled looks and seeing the shutting of screen doors as they passed. Similar experiences have been documented in public places like stores, restaurants and coffee shops.

Black men are often criminalized in public spaces – that means they are perceived as potential threats and predators. Consequently, their blackness is weaponized. Moreover, black men’s physical bodies are viewed as potential weapons that could invoke bodily harm, even when they are not holding anything in their hands or attacking. In fact, black people are 3.5 times more likely than white people to be killed by police in situations where they are not attacking nor have a weapon.

My research highlights that the social psychology of criminalization – the inability to separate concepts of criminality from a person’s identity or role in society – is important here. Often, physical features such as skin tone are used to guide attitudes, emotions and behaviors that can influence interactions between people of different races and lead to oversimplified generalizations about a person’s character. For black men, this means that negative perceptions about their propensity to commit crime, emotional stability, aggressiveness and strength can be used as justification for others to enact physical force upon them.

Signaling or survival?

Some black men attempt to make themselves less threatening. When it comes to jogging in white neighborhoods, some of the black men I spoke to wore alumnus T-shirts, carried I.D., waved and smiled at neighbors, and ran in well-lit, populated areas.

This is hardly surprising. Black men do this at work by thinking consciously about their attire, tone and pitch of voice, and behavioral mannerisms. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, many black men are going to great lengths to reduce criminalization by staying in the house, wearing colorful masks and even forgoing masks altogether.

Sociologists call it a signaling process. Black men call it survival.

An irony in the case of Ahmaud Arbery is that it has set in motion a campaign that could see more black men putting on their running shoes. The #IRunWithMaud social media campaign is encouraging people to jog 2.23 miles – a reference to the date on which Arbery was killed.

Editor’s note: This story was updated on May 7 following the arrests of Gregory McMichael and Travis McMichael.![]()

Rashawn Ray, Associate Professor of Sociology, University of Maryland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.